The Pittsburgh of 1960 was an incredibly different metropolis than the one we're attuned to now. Along the Monongahela River, the coke ovens burned and the ore ran hot. Construction of the 3,600 foot-long Fort Pitt Tunnels that connect the South Hills to the Fort Pitt Bridge had nearly been completed, while Frank Lloyd Wright eagerly sketched away at his Point Park concept drawings—an endeavor that ultimately was never approved. Bill Mazeroski's tie-breaking home run would garner the Pirates their first world series win in 35 years, while the Carnegie Institute of Technology – now known as Carnegie Mellon University – continued to gain esteem as an innovator in theater arts education. One noted alumnus of this program is George A. Romero, director of the seminal horror classic "Night of the Living Dead."

Although born and raised in New York before making Pittsburgh his home, Romero would come to exemplify the very nature of the Steel City with his do-it-yourself ethos, resilience and constant reinvention. While labeled a horror filmmaker thanks to his iconoclastic zombie creations, Romero's technical skill and idiosyncratic imagination put him in a class all his own. Like the laborer who forged steel from its raw materials, Romero was a worker in film, constantly redefining the role of the auteur. Romero's style continued to evolve from film to film, forming a utilitarian approach to filmmaking that utilized what was available in order to make each viewing experience unique. From the quick comic book style editing of scenes in "Night of the Living Dead," "Martin," "Dawn of the Dead" and "Knightriders," emerging as the fluid camerawork and long takes of "Day of the Dead," "Bruiser" and "Land of the Dead," with a segue way into an experimental found-footage style exemplified by "Diary of the Dead," Romero was always exploring possibilities not only in film but in new media as well. Comic books, novels, video games and interactive roleplay were additional media Romero used to share his unique vision with the public, all evidence of a revolutionary storyteller who refused to be bound to any one form of expression.

Although towering at 6'5", Romero was known for his gentle soul and affability, both of which helped him to find work in the Pittsburgh film and television industry. While a student at Carnegie Tech, he worked as an unpaid courier for the Pittsburgh Motion Picture Laboratory, delivering developed newsreel footage to stations like KDKA throughout the city. Already adept at student filmmaking from his time creating short films as a youth, Romero became enmeshed in the news and industrial film scene of Pittsburgh, learning from seasoned veterans how to edit quickly and shoot from the hip. During this time, Romero also worked as gopher on major Hollywood productions such as Alfred Hitchcock's 1959 classic "North by Northwest," but it was the film processing labs of Pittsburgh where Romero felt most at home.

Carnegie Mellon had a wonderful theatre department but film studies was just watching movies, watching Battleship Potemkin and talking about it. There was no equipment, no practical hands-on learning experience. But there were film labs in cities the size of Pittsburgh because the news was [shot] on film at that point. There were three big film labs that processed 8mm, 16mm and 35mm and I used to just go and hang out, and that's where I learned the basics; from these journeyman news guys and the editors who were cutting the newsreels.

George A Romero: The Sight & Sound Interview (February 2014)

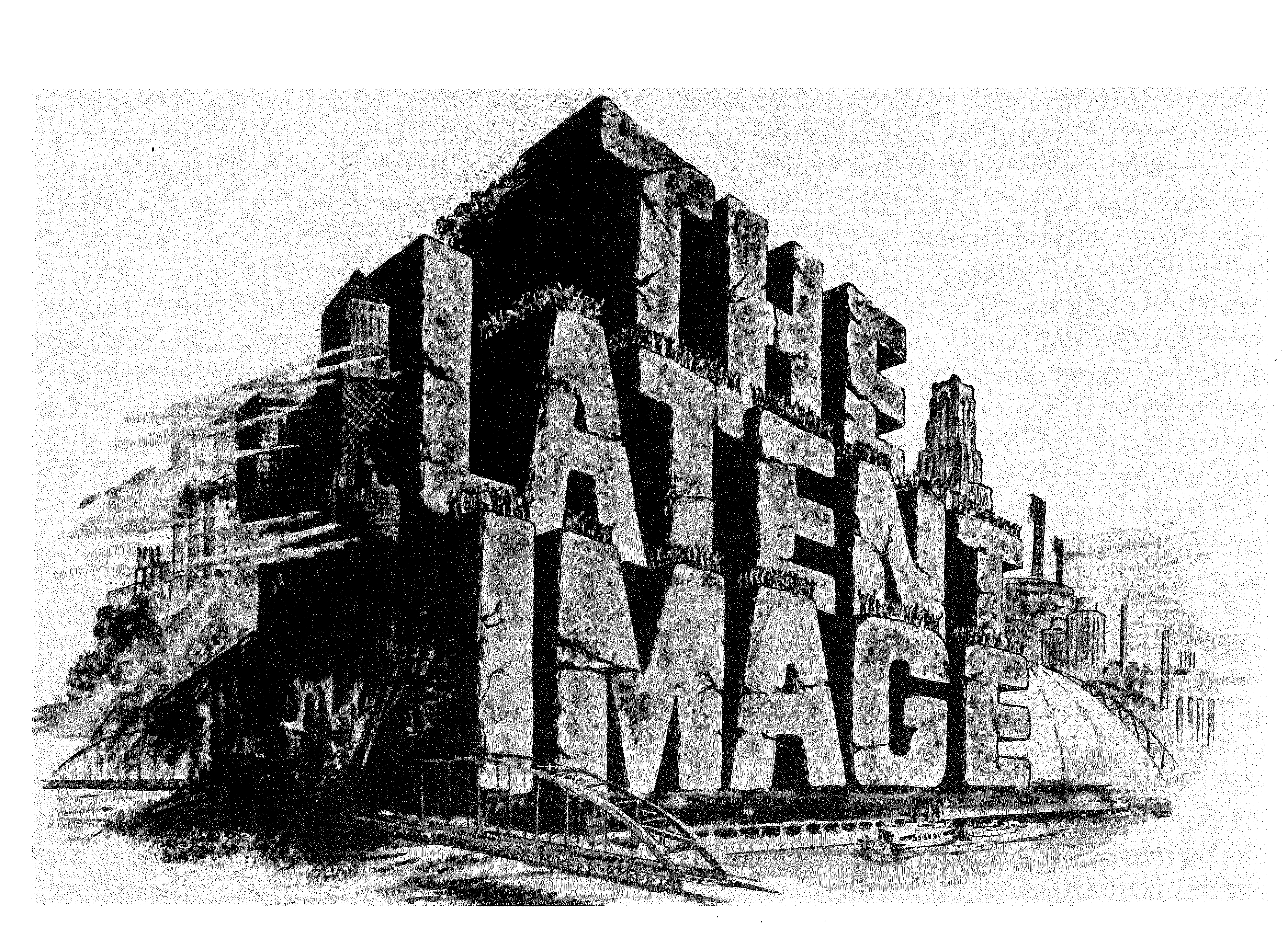

After leaving school, Romero joined up with fellow filmmakers Rudy Ricci and Russ Streiner to form The Latent Image, an independent commercial production house. Incorporated with a $20,000 loan from Romero's uncle, the company was very hand-to-mouth but kept alive through ingenuity and creative zeal. Originally housed in a Carson Street office within the South Side district, The Latent Image team created commercial spots for clients such as Iron City Beer, U.S. Steel and Heinz Ketchup, while also producing industrial shorts that won top prizes at the New York International Film Festival. One of Romero's first directing gigs was working on "Mr. Roger's Neighborhood," where he created the "Picture, Picture" segments for each episode. His first large-scale directorial work was "Mr. Rogers Gets a Tonsillectomy" (1968), an educational short where host Fred Rogers undergoes a surgical removal of the tonsils in an effort to help children defeat their fears. Rogers would continue to be a major supporter and friend to Romero throughout his life.

He was the first guy who would hire me. Everyone from Pittsburgh who I know from that period, who is still working in the business in any capacity, started with Fred. Fred was so supportive of people. He was a beautiful guy. He was the sweetest man I ever knew. What you see is what you get. That was Fred. In some ways he was still 10 years old. He was a wealthy guy, but very dedicated. He was a super wealthy cat — he could have just said 'Forget about it.' But he was dedicated to educating kids and telling them 'There's nothing wrong with you. I like you just the way you are.'

Romero interview, SFGate.com (May 2010)

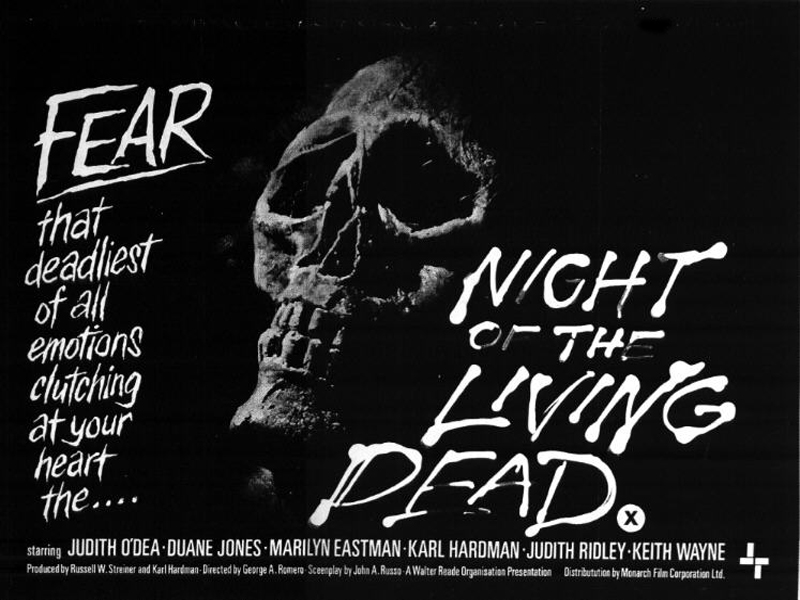

Romero's next project would drastically alter his future trajectory as well as that of the horror film genre. Released in 1968, "Night of the Living Dead" would be Romero's feature film directorial debut and come to exemplify a very transformative time in our nation's culture. In redefining the zombie mythos, Romero turned the zombie of Haitian folklore into reanimated corpses that feasted upon the flesh of the living, while creating a modern allegory about the political unrest that permeated the country. The 1960s was a time of deep divide. After the assassination of John F. Kennedy in 1963, a dark cloud grew over the nation's psyche and the youth counterculture began to grow. The civil rights movement saw victories in legislation to end racial segregation in the South in the mid-1960s, but the threat of racial violence never dissipated and urban unrest increased in the late 1960s. Romero's film touched on these themes in very symbolic ways, with the zombies serving as a metaphor for the new generation devouring the old, and the inclusion of one of the first African-American heroes in horror cinema. While Romero would claim in future interviews that many of these political undertones were coincidental, there is little question that the zeitgeist of the 1960s heavily influenced the film. This would spark similar themes of cultural criticism in Romero's filmic investigation of each subsequent decade: with the consumerism and decadence of the 1970s in "Dawn of the Dead," his dark and nihilistic view of the 1980s in "Day of the Dead" and his subversive take on class struggle and terrorism of the 2000s in "Land of the Dead."

My zombie films have been so far apart that I've been able to reflect the socio-political climates of the different decades. I have this conceit that they're a little bit of a chronicle, a cinematic diary of what's going on.

George A. Romero

As Romero progressed in his filmography, he would continue to defy convention. In an effort to avoid being pigeonholed as a horror film director after "Night of the Living Dead," Romero created two mainstream pictures, "There's Always Vanilla" (1971) and "Season of the Witch" (1972), before embracing the genre once again with "The Crazies" (1973) and "Martin" (1977). His long-awaited zombie follow-up "Dawn of the Dead" (1978) grossed $55 million worldwide on a $1.5 million budget, making it one of the most successful independent films of its time. Ever rebellious, Romero also chose to challenge the Motion Picture Association of America and release the film unrated, leaving his vision intact. He would make several transitions to other films and media throughout his career; creating the Arthurian motorcycle drama "Knightriders" (1981) along with excursions into other genre fare such as the Stephen King-scripted anthology "Creepshow" (1982) (filmed on location at Carnegie Mellon University), "Monkey Shines" (1988), "Two Evil Eyes" (1990), "The Dark Half" (1993), "Bruiser" (2000) and the television series "Tales from the Darkside" (1984-1988). Through it all he would return to his zombie creations whenever he could, establishing additional statements in his mythology with "Day of the Dead" (1985), "Land of the Dead" (2005), "Diary of the Dead" (2007) and "Survival of the Dead" (2009).

I don't try to answer any questions or preach. My personality and my opinions come through in the satire of the films, but I think of them as a snapshot of the time. I have this device, or conceit, where something happens in the world and I can say, "Ooo, I'll talk about that, and I can throw zombies in it! And get it made!" You know, it's kind of my ticket to ride.

George A. Romero

On July 16, 2017, George A. Romero passed away from lung cancer while listening to the score of "The Quiet Man," one of his favorite films. It stars John Wayne as Sean 'Trooper Thorn' Thorton, an ex-boxer from Pittsburgh who returns to his native Ireland to reclaim his family farm. Along the way he falls in love, is pitted against an angry oppressor who wants the farm for himself and must ultimately fight to make a new life in a foreign land. Until the day he died Romero was a lover of cinema whose stories and imagery were sometimes at odds with the status quo, but through creative innovation and a strong sense of individuality, he was able to create something special and new. Romero once said that in filmmaking, 'Everybody knows the rules, even though some break those rules.' George A. Romero not only knew the rules and broke them, but he created some new ones too.

by Andy Prisbylla, Library Associate