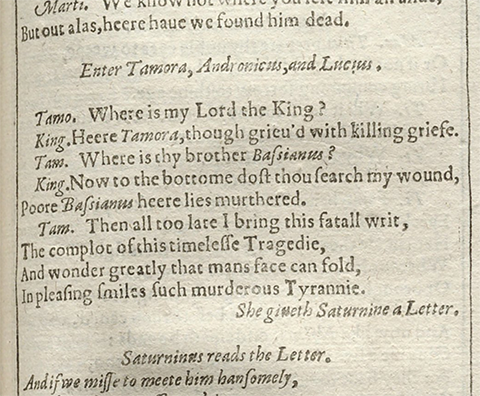

Figure1. From Folger Library Folio 5, Tragedies page 39 [dd2r] (STC 22273 Fo.1 no.05)

Among the rarities kept in Carnegie Mellon University's Special Collections Library is a large book of plays, its terse and unfussy title belying its importance: ‘Mr. VVilliam Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies.' The First Folio, as it's more reverently known, remains the object of ardent scholarly and cultural interest, and the Libraries' copy (one of 235 that survive worldwide) features regularly in class visits to Special Collections.

This semester has been atypical, of course, and with Hunt Library closed, these visits have been placed, temporarily, on hold. However, multiple copies of the First Folio are now accessible online in the form of digital facsimiles. On Friday, April 3, Professor of English Christopher Warren's Shakespeare course convened in a virtual Zoom classroom, where together we looked at two of the Folger Shakespeare Library's digitized First Folios. This forced experiment in looking at old books on a scattered network of screens is an example of the kind of collections-focused instruction that remains possible, even during mass quarantine.

While it's impossible to simulate the heft and presence of the First Folio, a high-resolution digital surrogate offers unique opportunities and affordances; this is a book that rewards close looking.

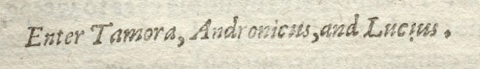

Figure 1, Detail.

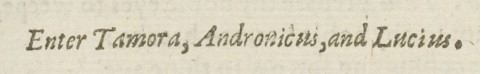

Take, for example, this passage from the second act of Titus Andronicus as it appears in the Folger's Folio number 5 (fig.1) Using Zoom's screen-sharing function, we enlarged this page, examining the passage to reveal an inconspicuous peculiarity: in the middle of a stage direction marking the entrance of Tamora, Andronicus, and Lucius appears an inverted letter ‘i' (fig. 1, detail). To further confuse things, in the second First Folio we examined (Folger Folio number 68; fig. 2), this same ‘i' appears righted, its top dot (called a ‘tittle' by typographers) exactly where it should be. What gives?

Figure 2. The same stage direction in Folger Library Folio 68 (STC 22273 Fo.1 no.68)

The case of the turned-i, it turns out, is less than eye-turning. This kind of anomaly in typesetting is common in early printed books, even in copies of the same edition. But how did this wayward ‘i' right itself? Well, it didn't really, at least not unaided: in the Folger's Folio number 5, the printer made a mistake, placing the tiny piece of metal that bore the letter ‘i' upside down in the press. After several copies of the sheet of paper bearing this passage (and the upturned ‘i') had been printed, a copy-editor spotted the mistake, ran across the room (we assume), and demanded that his colleague rotate the ‘i' before printing another copy—and so he did.

As a scholar and curator of early printed books, I'm fascinated by this kind of typographic oddity for a host of reasons, but the reason I stressed in my time with Professor Warren and his students has to do with chronology: from this evidence, we know that the page containing the turned ‘i' was printed before the corresponding page with the upright ‘i'. In other words, evidence as minute as a wandering tittle can help us reconstruct how a particular book made its way through the labyrinth of a seventeenth-century printshop.

All of this invites the question: is this same ‘i' upright in the Libraries' copy of the First Folio? I have to admit, I don't know. I plan to check as soon as Special Collections reopens.

Samuel Lemley, Curator of Special Collections