Notes on the First Official Printing of the US Bill of Rights (1792)

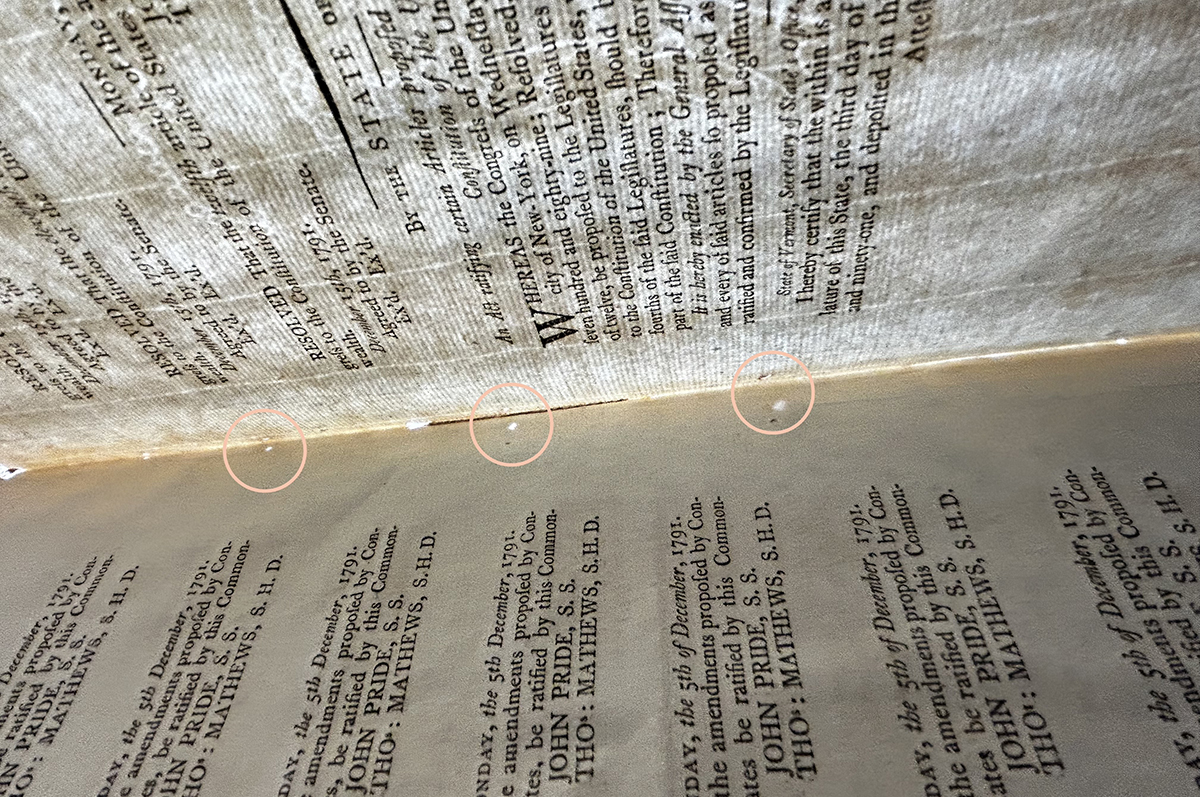

Evidence of stab-stitching in the Posner copy, CMU Special Collections.

by Sam Lemley, Curator of Special Collections

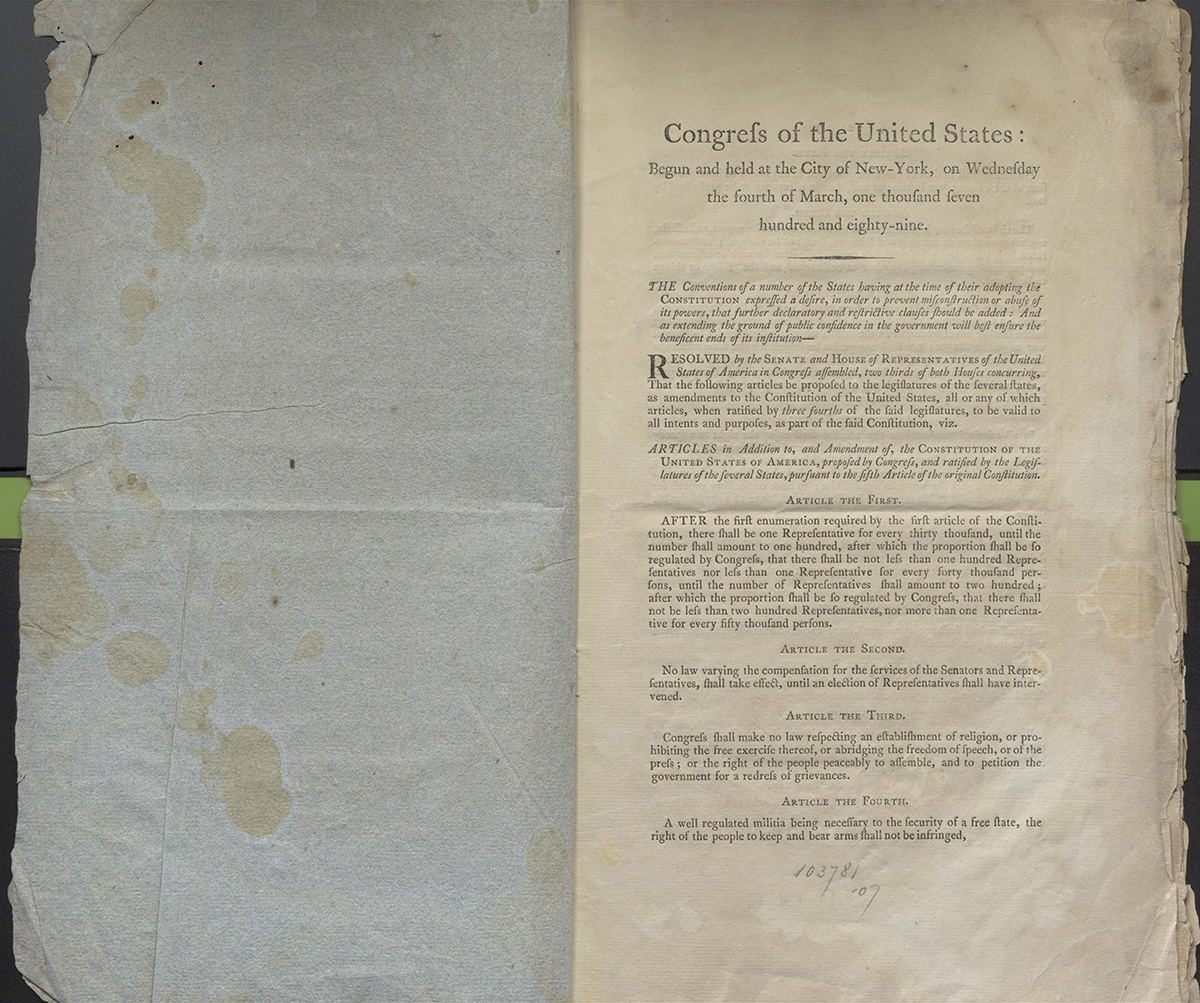

In CMU Special Collections is a copy of the US Bill of Rights printed in Philadelphia by Francis Childs and John Swain. The document is undated, but is usually assigned to January or February 1792. This edition is a grail of Americana: it is the first appearance of the Bill of Rights in print following ratification in 1791. It is also perhaps the rarest item in Special Collections. Only five copies are known to survive: one at the Maryland State Archives, another at the American Antiquarian Society, and another at the Library of Congress. A fifth copy is in private hands and was last sold at auction in 2002. Special Collections’ copy is part of the Posner Memorial Collection, deposited with the Libraries in 1978 in memory of Henry Posner Senior (d. 1976), who purchased his copy from antiquarian bookseller H.P. Kraus in 1963.

I wrote about the historical significance of the Posner Bill of Rights in a previous post and described the legislative process that preceded ratification in an episode of “Coffee with the Curator” in 2020. But for Constitution Day 2024 I want to return to the document itself and examine the Posner copy against the three copies held at other institutional collections — namely, those at the Maryland State Archives (the MSA copy), the American Antiquarian Society (the AAS copy), and the Library of Congress (the LOC copy). Unsure of what I’d find, this post offers a play-by-play account of the type of bookish sleuthing that’s possible in Special Collections.

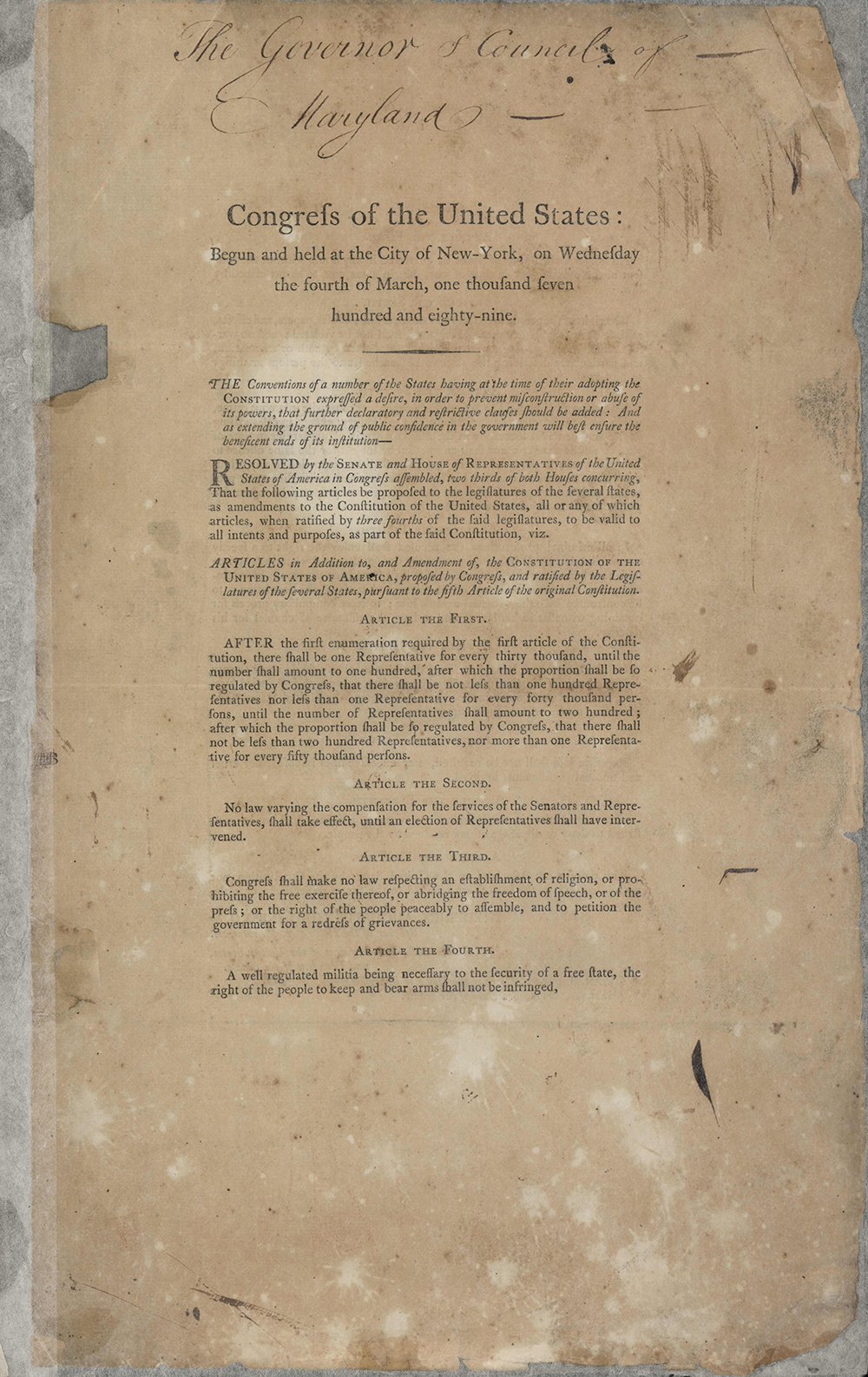

Four copies — one examined physically, three digitally — of the 1792 Bill of Rights show that the edition survives in two forms. The following illustration collates the first page of the AAS copy and the MSA copy and shows that the margins of the MSA copy are significantly larger than those in the AAS copy. Its lower margin is especially spacious, mottled by time and splotches of ink.

Images courtesy of the Maryland State Archives (left) and the American Antiquarian Society (right).

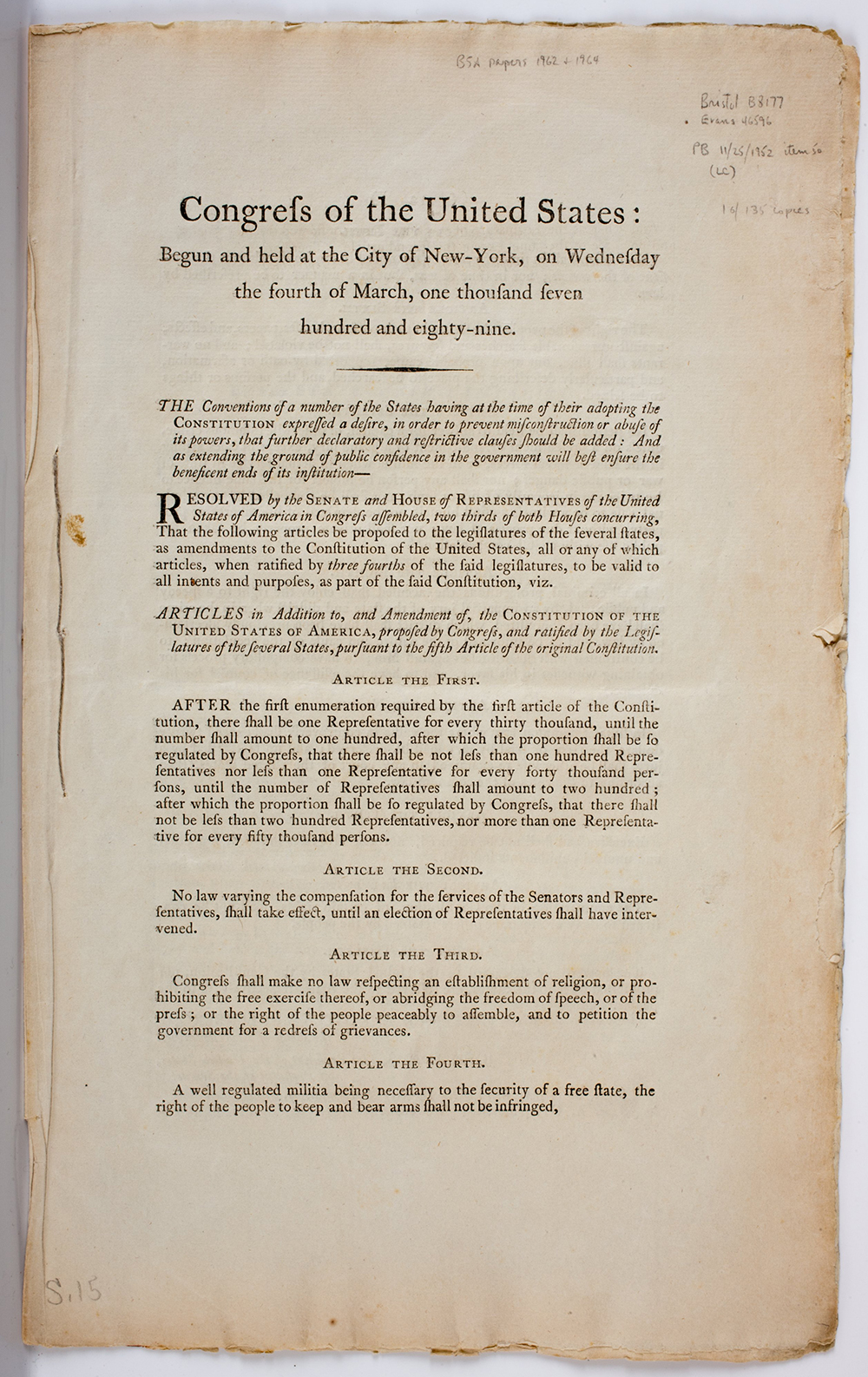

The difference in size is not the result of trimming. The sheets of the AAS and LOC copies retain their irregular “deckled edges” — a result of the papermaker’s slurry of macerated linen rags seeping through the frames (“deckles”) of the molds used to manufacture sheets of paper in the eighteenth century. The outer “fore” edge as well as the top and bottom edges of each leaf in the MSA and AAS copies display this characteristic, crenulated “deckling”; the sheets of these copies are therefore near to their original dimensions.

Images courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society (top) and the Maryland State Archives (bottom).

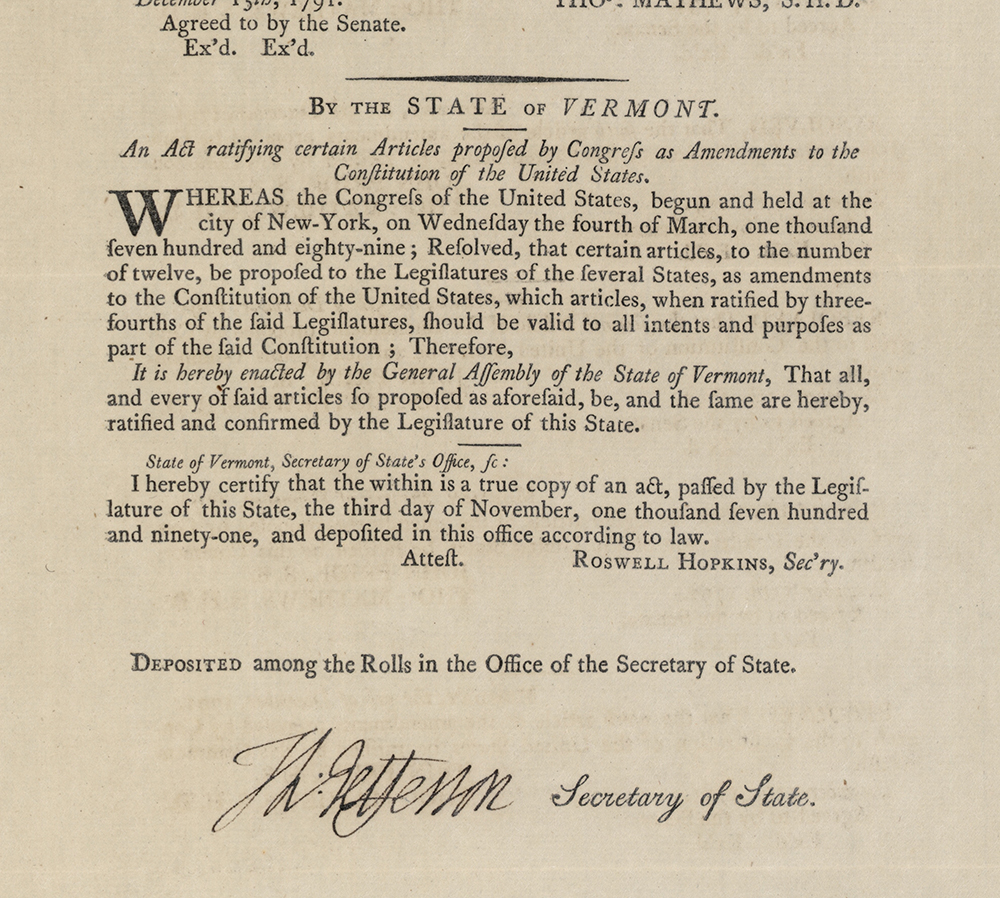

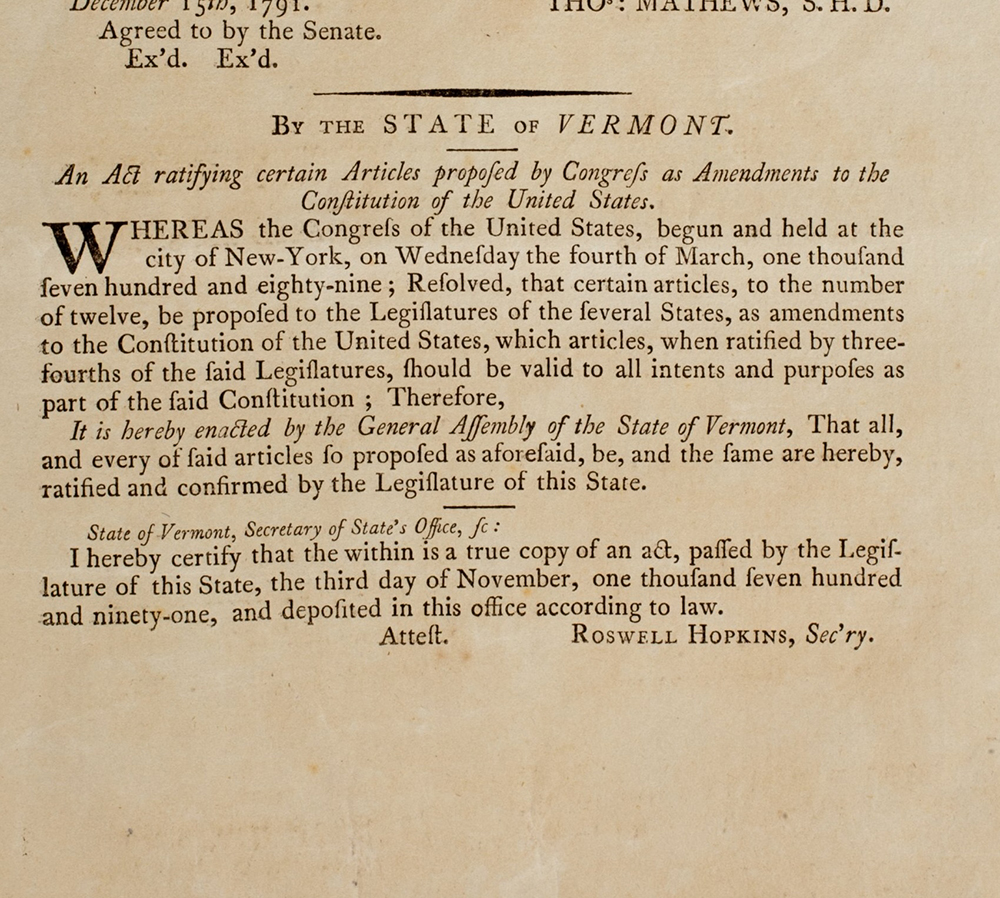

We’re already on thrilling, unprecedented ground: no bibliography of early American imprints or published description of the 1792 Childs-Swain Bill of Rights notes that the edition was printed on two stocks of paper of vastly different size. But there is another difference between these two forms (or “issues”) of the 1792 Bill of Rights. On the final page of the MSA copy, below Vermont’s notice of ratification, appears a single-line of printed text, “Deposited among the Rolls in the Office of the Secretary of State”. Under this appears the manuscript signature and attestation of Thomas Jefferson next to his official title, printed in a cursive type (“Secretary of State”). This same statement and its accompanying attestation are pointedly absent in the small-paper copies I examined (LOC, Posner, and AAS).

Images courtesy of the Maryland State Archives (left) and the American Antiquarian Society (right).

A provisional narrative begins to emerge from this evidence. The Office of the Secretary of State recorded payment of $30 for 135 copies of the “ratification of amendments to Constitution” to the printers Francis Childs and John Swain in July 1792. The paper for these 135 copies cost an additional $3.12. It seems likely that Jefferson instructed Childs and Swain to print at least 26 copies on larger, finer paper — two copies for each of the US states, which were then only thirteen in number. Jefferson enclosed these copies in a letter sent on 1 March 1792 to the states’ Governors: “I have the honor to send you herein enclosed two copies, duly authenticated, of [...] the ratifications, by three fourths of the Legislatures of the several States, of certain articles in addition to and amendment of the Constitution of the United States.” Jefferson’s note indicating that both copies were “duly authenticated” suggests that each bore — like the MSA copy — Jefferson’s signature; it also suggests that all “authenticated” copies were printed on the same, larger stock of paper. The MSA copy, superscribed in manuscript on its first page to “The Governor & Council of Maryland,” is one of these official, “authenticated” copies, and apparently the only one to survive.

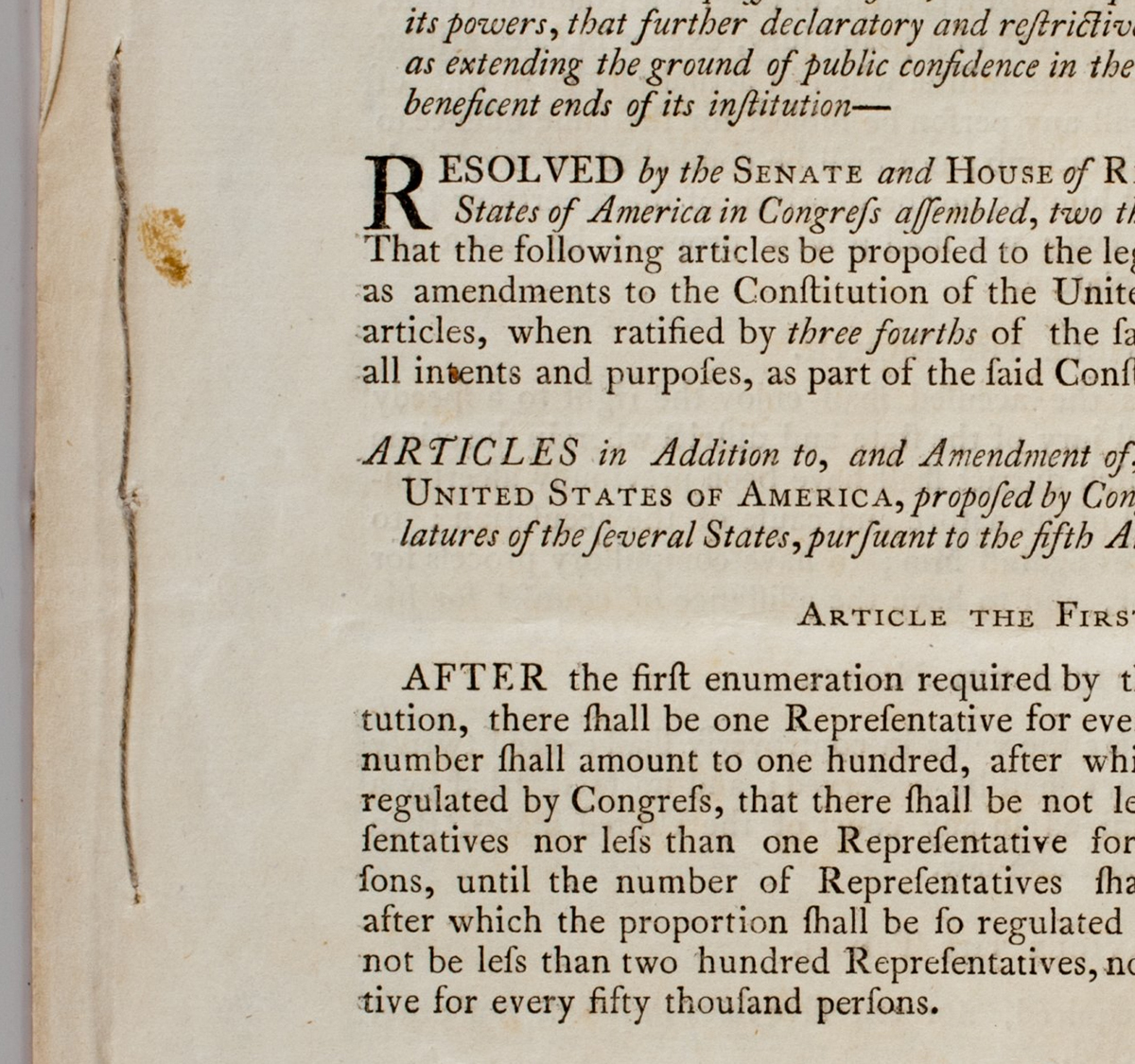

All five surviving copies of the 1792 Bill of Rights also contain evidence that they were at one point stab-stitched. Stab-stitching was often a temporary fix, a rudimentary method of binding together folded sheets that could be replaced by a more durable binding or enclosure. But as Zachary Lesser reminds us, the holes left by stab-stitch threads, even after their removal and replacement, “provide an important piece of bibliographic evidence for how a book was first sold” or otherwise distributed.

Both the LOC and AAS copies miraculously retain their original binding cord — a length of string threaded through three holes “stabbed” along the folded edge and knotted at the back of the pamphlet’s final leaf.

The original stab-stitch thread as preserved in the AAS copy. Image courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

Although the Posner copy was at some point rebound in a leather binding (its spine preserves fragments of this later binding, from which it was removed sometime before Henry Posner Senior purchased it in 1963), close inspection reveals that it, too, was once stab-stitched: near its folded edge are three holes, their placement similar to those in the AAS copy (the illustration shows pinpoints of light passing through these holes in the Posner copy).

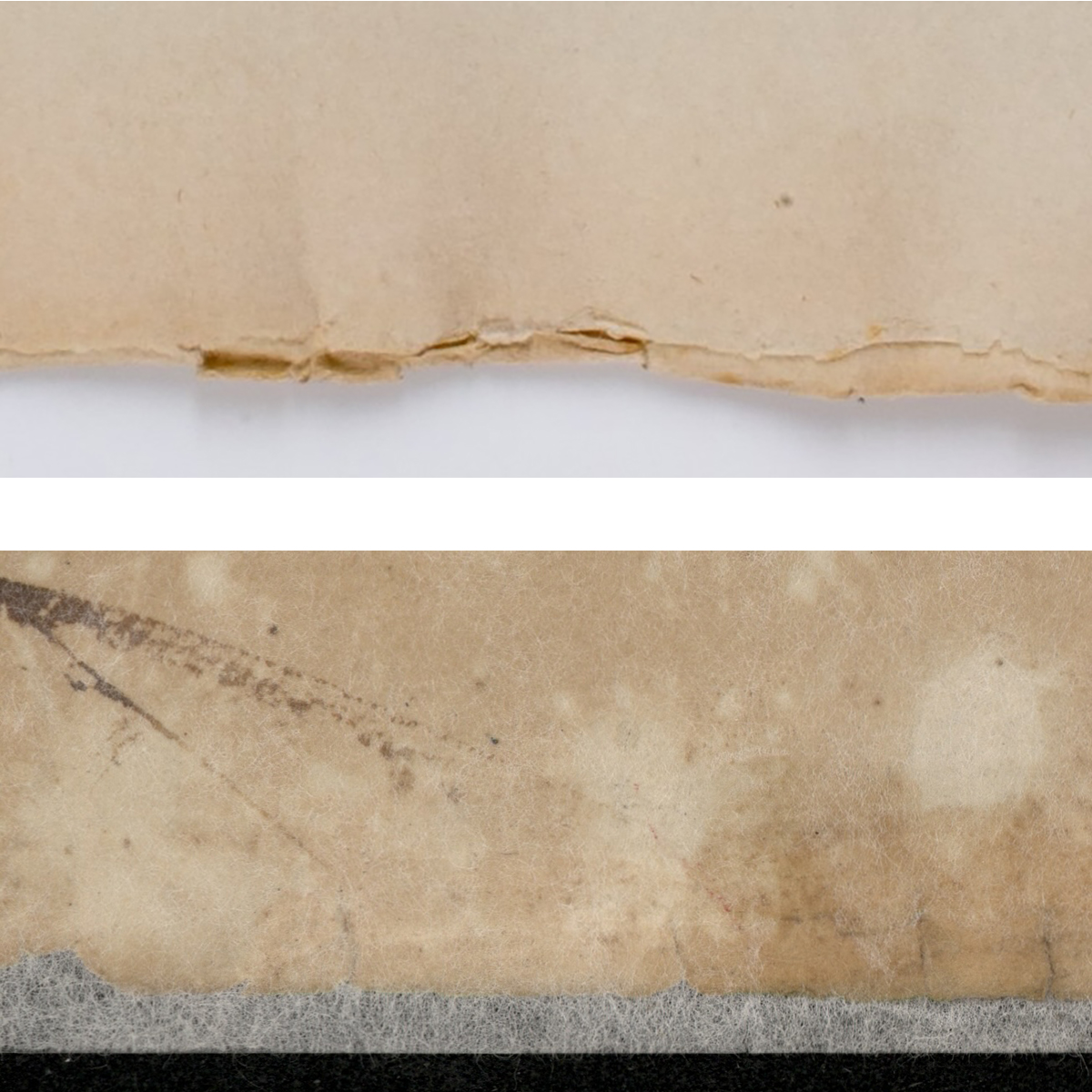

The MSA copy also bears evidence of stab-stitching. Although recently conserved — each leaf is encased in a translucent cocoon of archival paper — at least one of the original stab-stitch holes remains visible on the first leaf of the MSA copy, indicating that Jefferson’s “authenticated” copies were also sewn together before they were sent to the states.

Both the LOC copy and the copy sold at Christie’s in 2002, meanwhile, are preserved in blue paper wrappers — a sort of eighteenth-century dust jacket tacked to each copy by the same stab-stitch thread that held their sheets together. While both the Posner and AAS copies lack this paper wrapper, the relatively unmarred appearance of their first pages suggests that they were at some point protected by a similar covering. In contrast, the outer leaves of the MSA copy are stained, torn, and discolored, implying that they were never wrapped or bound.

It seems, then, that Jefferson’s instructions to Childs and Swain included notes on how the two issues of the 1792 Bill of Rights — both large- and small-paper copies — were to be handled after printing. Intended for enclosure in his letter to the states’ Governors, the larger “authenticated” copies perhaps did not require stab-stitched covers, while the smaller unauthenticated copies may have been slated for sale or public distribution and thus warranted the protection of paper wrappers.

Evidence of stab-stitching in the MSA copy; image courtesy of the Maryland State Archives.

The original blue-paper wrapper; image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Rare Book Division.

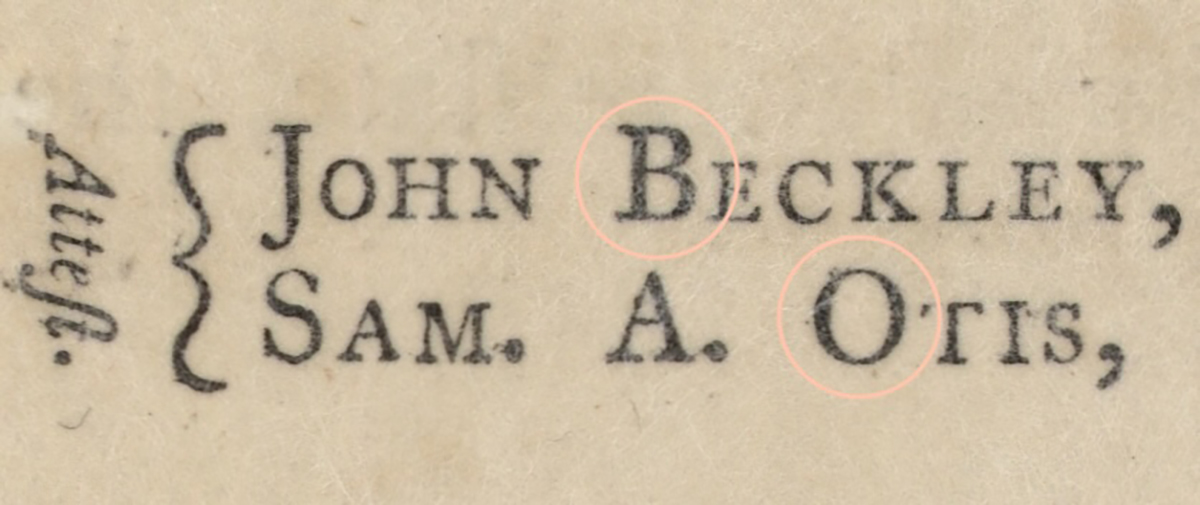

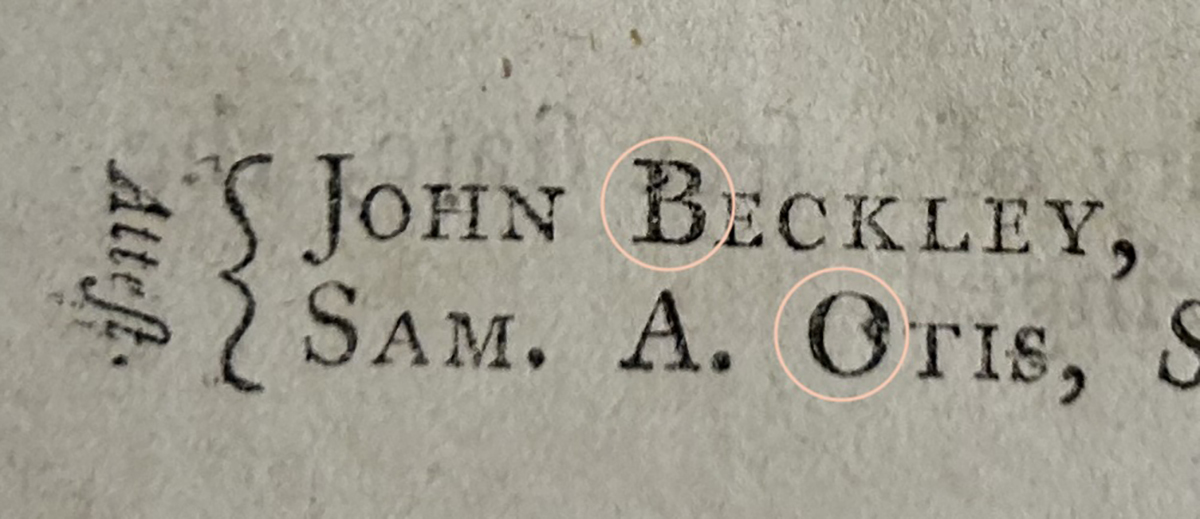

Perhaps the most striking evidence I found while examining these four copies of the 1792 Bill of Rights is a subtle variant in the text. On the second page of the AAS, LOC, and Posner copies, the printed attestations of John Beckley and Samuel A. Otis display two pieces of damaged type. Both the B in Beckley and the O in Otis are broken. These same letters are undamaged in the MSA copy.

How to explain this difference?

In the eighteenth-century, pieces of type, or type “sorts”, were cast in metal, each carrying a reversed image of a single character. These metal sorts were placed on the press and inked to impart their image (again reversed) onto paper. Made of a relatively malleable lead alloy, type sorts were often damaged during presswork, crushed or bent by the heavy action of the press or spoiled by debris that settled on the types during printing.

This small accident of the press — a fractured B and O — thus offers a window onto the past, revealing that the MSA copy — and likely the entire run of Jefferson’s large-paper, “authenticated” issue — was printed before the smaller AAS, LOC and Posner copies; before, that is, the B in Beckley and the O in Otis were broken.

The undamaged B and O as they appear in the MSA copy.

The damaged B and O in the Posner copy.

All of this speaks to the fact that historical books and documents have much to tell us; and that bibliographically significant evidence can be as inconspicuous as a hole through paper or a minutely damaged uppercase O.

It’s this idea of the unexpected that I aim to impart to CMU students when they visit Special Collections. I ask them to consider the material fact of the objects in front of them. Far from simple vessels of history or objects marking important milestones in science or culture, books carry traces of the people and materials that took part in their making.

A visit to Special Collections is a cultural experience not unlike visiting a museum. But I also invite my students to consider and interpret things as self-evident and unprepossessing as holes and stains on paper. I want them to feel included in the process of analysis and discovery that is such a thrilling part of my day-to-day work. The beauty of this approach is that it assumes no cultural or even linguistic expertise: books printed in obscure languages and strange scripts become newly accessible, and students who might otherwise be intimidated by the reverent hush of Special Collections are instead invited into the fold as my collaborators and co-conspirators. When the alchemy of this encounter works, it works brilliantly. And as this post makes clear, there are plenty of discoveries that remain to be made.

CMU Special Collections, recently and sumptuously rehoused in the Posner Center, is open by appointment for research or class visits. And while Special Collections is undergoing renovation, recataloging, and reshelving over the next academic year, my aim is to put the Posner copy of the 1792 Bill of Rights on public display next September to mark Constitution Day 2025 — with more bibliographical findings to share, I hope. Stay tuned! And thanks for reading.

1 Christie’s, Live Auction 1060, Printed Books and Manuscripts, Lot 225 (19 December 2002).

2 “VII. Contingent Expenses of the Department of State, 1790–1793, 14 January 1790–31 December 1793,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-17-02-0099-0008. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 17, 6 July–3 November 1790, ed. Julian P. Boyd. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965, pp. 359–379.]

3 “Circular to the Governors of the States, 1 March 1792,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-27-02-0774. [Original source: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 27, 1 September–31 December 1793, ed. John Catanzariti. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 815.]

4 Zachary Lesser, Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes: Shakespeare in 1619, Bibliography in the Longue Durée (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021), p. 73, quoted.