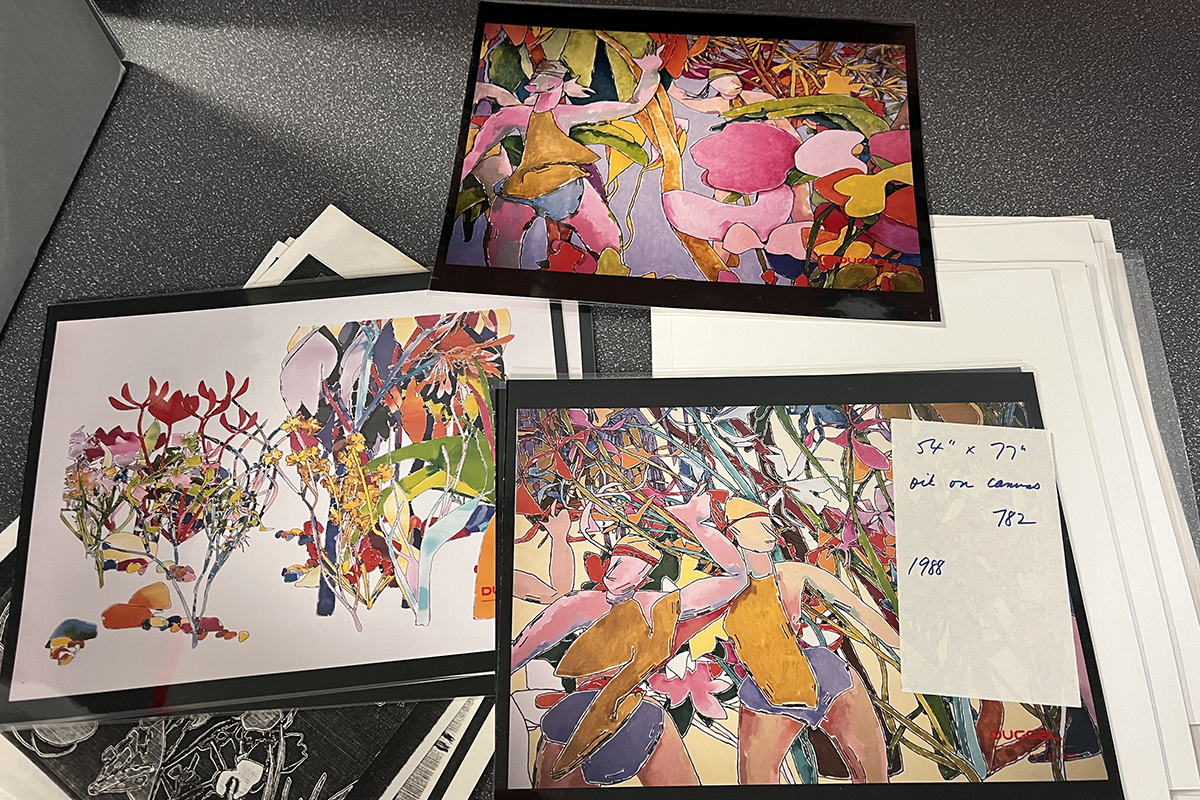

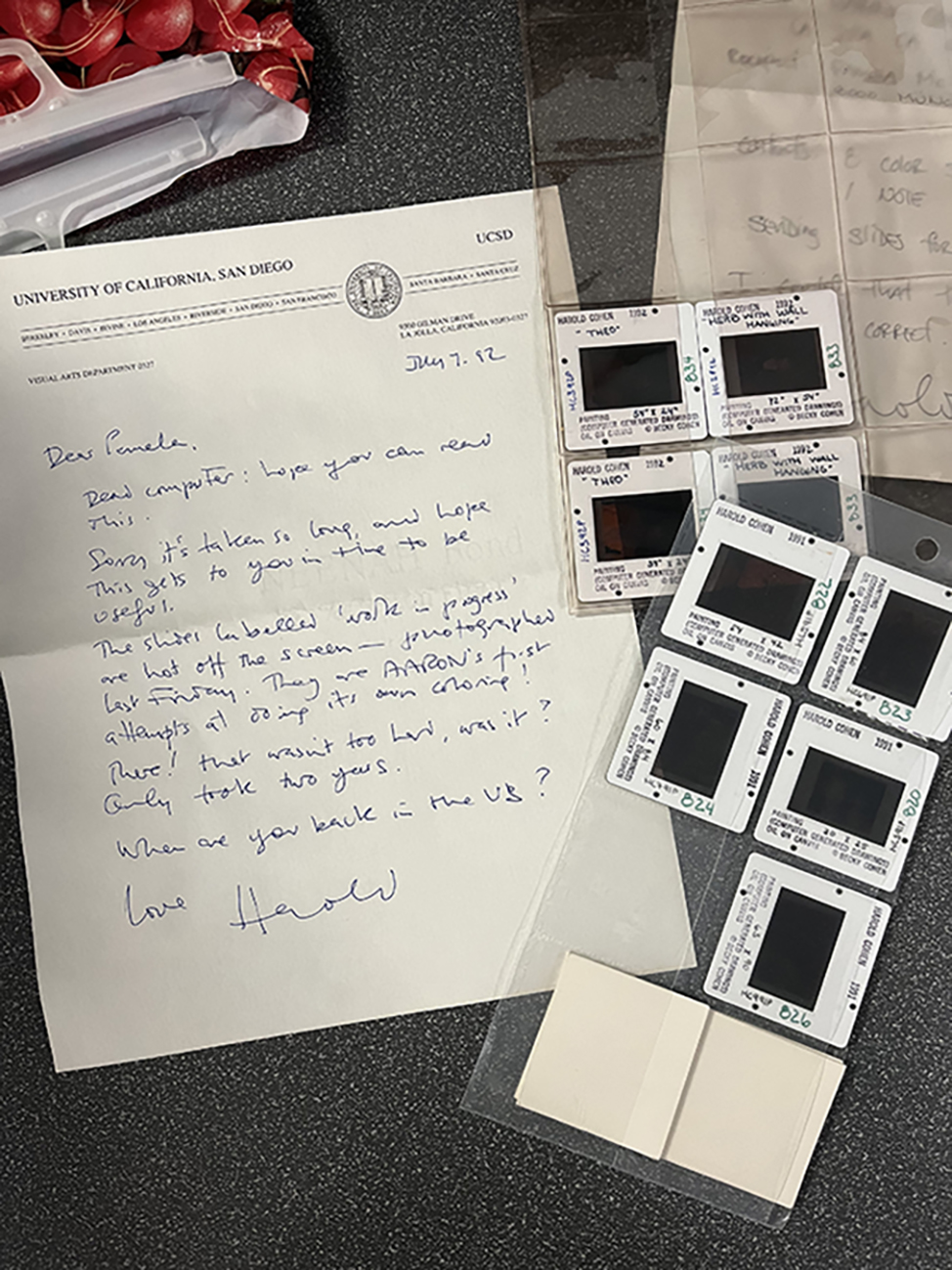

Letters and images from Pamela McCorduck's papers, held by the University Archives.

Pamela McCorduck, author and generous friend to Carnegie Mellon University, was a close observer at the dawn of artificial intelligence. Her husband Joseph Traub worked alongside computer science pioneers Allen Newell and Herb Simon in CMU’s Computer Science Department, and she wrote some of the first novels and histories about AI during that time. An influential, creative mind in the field, McCorduck was also an appreciator of the scientific and aesthetic value of computer-generated art.

Thanks to McCorduck’s personal collection, gifted to Special Collections in 2018, the Libraries is home to a significant collection of AI art by groundbreaking artists Harold Cohen and Lillian Schwartz. The 19 pieces held in the collection are early, unique examples of the potential for creativity and innovation at the intersection of computer science and the humanities.

“McCorduck was a pioneer. She recognized the cultural and technological significance of Cohen and Schwartz’s work and the radical effect that computers would have on contemporary art,” Curator of Special Collections Sam Lemley said. “It's a real privilege to learn about these fields in working with these materials, and to share some of those stories with CMU students and members of the public.”

A Groundbreaking Process

In the late 1960s, when McCorduck first crossed paths with Cohen at AI conferences in the years following his foray into computer programming, there was no Chat GPT or DALL-E to almost instantly return information scraped from a vast wealth of text and images across the internet. In order to generate written or visual content with a computer, a creator had to rely on code that explicitly spelled out rules and conditions for the computer to follow.

AARON, Cohen’s AI program for artmaking, was the first of its kind in the world.

But Cohen was at his core an artist, not a computer scientist — he was an accomplished painter before turning to programming — and he was interested not so much in scientific discovery, but in illuminating the process of making art. He set out with a goal of answering what he thought was a simple question: what are the minimum conditions under which a set of marks will function as an image?

In the first phase of the program, developed between 1973 and 1978, AARON was only capable of generating simple but evocative shapes. Over the next decade, the program started to learn a primitive sense of perspective, understanding more sophisticated representations of visual space until it could create figures that reflected a fully three-dimensional knowledge base beginning around 1989.

From the early days, McCorduck saw value in Cohen’s iterative, increasingly sophisticated collaborations with his machine. She was a supporter of his work, purchasing a number of paintings over the years. These were displayed proudly on the walls of her home, and would eventually come to be included in the gift to the Libraries.

She also published a biography of Cohen in 1991, titled “Aaron’s Code.”

“By independently inventing and later learning from techniques of the scientific field called artificial intelligence, Cohen has heroically expanded the boundaries of art,” she wrote in the biography. “Writing every line of Aaron’s code himself, he has, Renaissance-style, put science in the service of art in a way that no casual dabbler with user-friendly, prepackaged software could possibly hope to achieve.”

Though Cohen’s work never brought him to Carnegie Mellon — he spent most of his career teaching at the University of California, San Diego — the AI world was a relatively small community, and AARON made an impact on CMU’s experts as well. That same year, Simon weighed in on the merit of Cohen’s program.

“Neither Harold Cohen nor anyone else can predict what Aaron is going to draw (although certain characteristics of its style can be predicted),” he wrote in a review of McCorduck’s book. “Harold Cohen is the programmer, but is the programmer more than a teacher? And does creativity lie in the teacher or in the artist he or she has trained (or, in this case, programmed)?”

Alternative Innovation

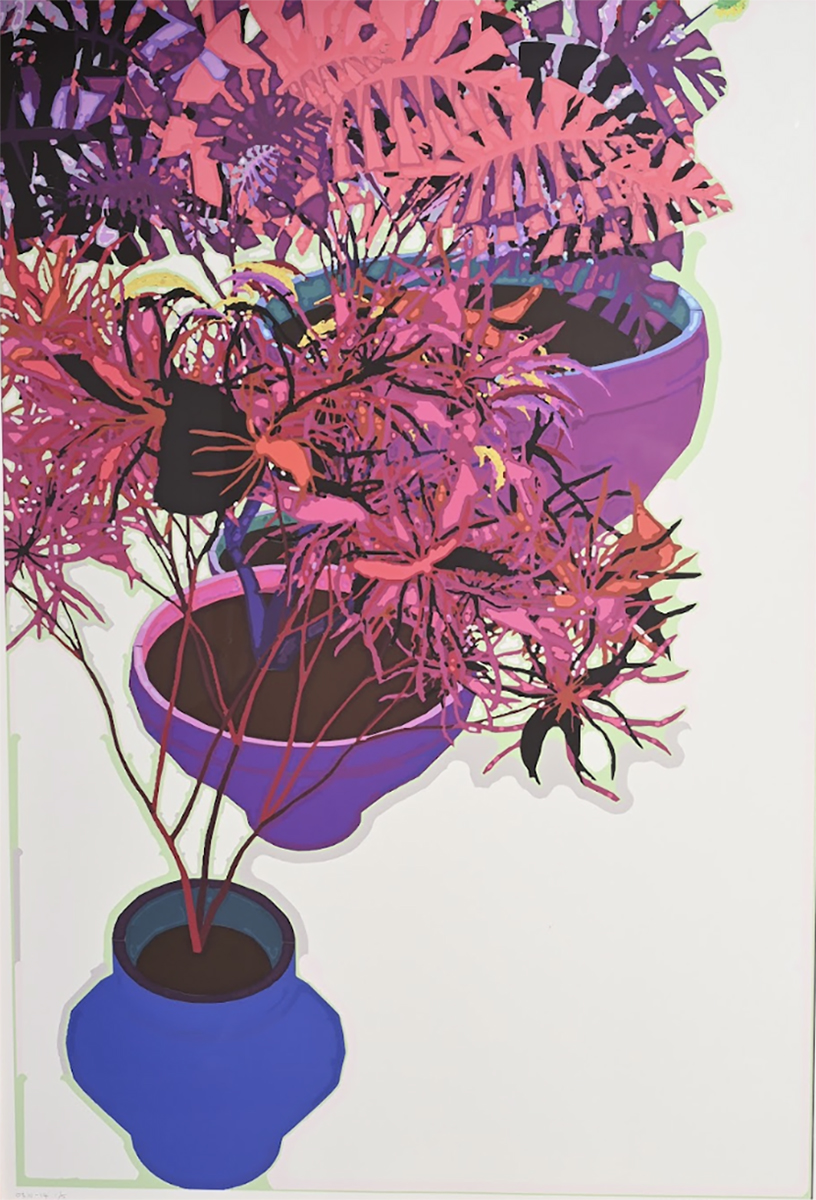

Schwartz’s work is different from Cohen’s, but no less pioneering when it came to expanding how a computer could contribute to the process of making art.

In the 1960s she joined the Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.) group, collaborating with other artists and engineers to introduce tools like video projection, wireless sound transmission, and other experimental mediums to the artistic world. She was also a “resident visitor” at Bell Laboratories, working with engineers on a series of computer-animated films. Over the years, she collaborated with NASA scientists, statisticians, chemists, and more, borrowing data from satellites, the movements of atoms and molecules, and elements of historic paintings by artists like Leonardo da Vinci to create her imagery.

McCorduck knew Schwartz personally as well — notes in her journals, held by the University Archives, record dinners throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s where the two discussed art, technology, and what could be achieved through a combination of the two. Schwartz’s works in the collection complement Cohen’s collaborations with AARON, showcasing the artistic capabilities of other contemporary tools, and the value of combining traditional art and experimental processes to create new innovations.

"Big MOMA" by Lillian Schwartz, 1984. Potential commission in honor of a new museum wing in The Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Celebrating Interdisciplinary Connections

In Special Collections, Lemley is working to build a leading academic resource in the history of computing, cryptography, and robotics. This narrow focus for the collection reflects Carnegie Mellon’s unique history and individual strengths.

In addition to Cohen and Schwartz’s paintings, the Traub-McCorduck collection contains more than 50 calculating machines, letters, and books — as well as two World War II Enigma cipher machines. It also includes the first commercially produced mechanical calculator, and rare books by Charles Babbage, the 19th century mathematician considered by some to be a "father of the computer."

Simon’s library, another holding in Special Collections, further zeroes in on key AI trends and developments. Special Collections also holds the library of Newell, Turing-award winner and co-developer (with Simon and Cliff Shaw) of the Logic Theorist (1956), recognized as the first computer program capable of automated reasoning. The Newell Library of Artificial Intelligence comprises some 1,800 volumes that document Newell's research interests in AI, chess play, game theory, and computer graphics.

But Special Collections is also an interdisciplinary space that serves as a resource for community members across campus — not just those studying science and technology, but also those researching the arts and humanities.

In the collection of Charles Rosenbloom, there are significant documents to the history of music, including first editions by Beethoven and Bach. There’s the Frances L. Hooper Collection of artwork by Victorian illustrator Kate Greenaway, one of the most extensive in the world. There’s also a painting by Harlem Renaissance painter Jacob Lawrence, part of a series of works held in major collections like the Museum of Modern Art and the White House. And Special Collections holds a first edition copy of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein,” complete in its original binding, along with a copy of Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623), the earliest comprehensive gathering of Shakespeare’s plays in print.

In the paintings by Cohen and Schwartz, art history and the history of computer science come together in a powerful representation of the interdisciplinary achievements Special Collections celebrates.

In the paintings by Cohen and Schwartz, art history and the history of computer science come together in a powerful representation of the interdisciplinary achievements Special Collections celebrates.

“Special Collections crosses formats and disciplines. It's incredible, for instance, to have in the same collection some of the earliest books on artificial intelligence — including offprints of articles by Alan Turing and seventeenth-century treatises on robotics and automata — alongside these paintings generated by way of Cohen's collaboration with AARON,” Lemley explained. “As Pamela McCorduck knew well in planning her gift, this diversity and scope allows CMU Libraries to tell uniquely inclusive and engaging stories about the history of AI, computer art, and the history of computing more broadly.”

Letters and images from McCorduck's papers, held by the University Archives.

Cohen’s Legacy Continues

Modern variations of AI art are becoming increasingly mainstream with the availability of text-to-image models like DALL-E, and Cohen’s art in particular is gaining popularity as a trailblazer. His work is currently featured in an exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, which runs until May 19.

“Cohen's artworks are truly pioneering and mark the inception of the AI art era we are now familiar with. It's a pivotal moment urging us to cultivate a cooperative relationship with our new enigmatic neighbor, AI,” said Eunsu Kang, a visiting professor of art and machine learning in the Machine Learning Department. “Undoubtedly, Cohen's work stands as one of the most significant contributions to art history, reflecting a paradigm shift towards collaborating with non-human agents in art creation.”

Cohen’s legacy is continued in innovative projects underway at CMU. One example is FRIDA, a robot painting project at the Robotics Institute (RI) that was inspired by Cohen’s work with AARON. The project is led by Jean Oh, an associate research professor in the RI and the head of the Bot Intelligence Group (BIG), Jim McCann, an associate RI professor who runs the Textiles Lab, and Peter Schaldenbrand, a Ph.D. student in the RI. Most recently, the team created the Collaborative FRIDA (CoFRIDA) robot painting framework, which can co-paint by modifying and engaging with content already painted by a human collaborator.

“To me, the art that impresses me the most in AARON lies in the beauty of the rules that Cohen designed in such a precise and delicate way,” Oh said. “Our current work in FRIDA is more focused on creating real-world art using robotics — some aesthetic or artistic quality is achieved mostly by serendipity, which I call ‘bounded aesthetic.’”

In the coming months, Special Collections aims to catalog and photograph Cohen’s work, making it accessible to researchers and the CMU community for the first time. With Cohen's centennial year approaching in 2028, Lemley hopes there will be additional opportunities to connect Cohen with the rare books and artifacts in the collection that illustrate the history of AI and computer-generated art.

“35 years after McCorduck’s book on Cohen, the questions she asked remain profoundly important — even urgent. The legacy and meaning of Cohen's work is still evolving,” Lemley said. “Libraries and museums hold the material and archival record that will help us make sense of where we've been and where we're headed. McCorduck's gift to the Libraries ensures that CMU Libraries is very much a part of that conversation.”

by Sarah Bender, Communications Coordinator