As the fall semester continues to ramp up, my time as the Posner intern is coming to an end. For my last blog post, I’d like to share one of my long-term projects and talk about how the history of computing is represented and curated in CMU’s Special Collections.

In addition to the many books in regular circulation that students can check out, most university libraries include special collections of non-circulating material. Special Collections is exactly what it sounds like: books that are older, rarer, more fragile, or historically significant, and that deserve to be set aside. Given what kind of university CMU is, it might be unsurprising that its Special Collections holdings focus on the history of science, technology, and especially computing. But aside from taking years to master the field and its history, how can we identify which books deserve to be preserved as important documents in the history of computing? Fortunately, others have already done the work for us. Over several decades, the antiquarian bookseller and historian of science Jeremy Norman built a comprehensive collection of texts on the history of computing and published a catalog of the collection, The Origins of Cyberspace (2004). This book is, basically, a list of many of the important works in computation from the 1600s to the 1970s, and it’s a great starting place for figuring out what might be added to CMU’s Special Collections to fill gaps in its holdings in the long history of computing.

Between 2004 and today, the history of computing has become a hot field, more people have realized the importance of computational technology in world history, and significant historical texts in the field have gotten harder and more expensive to acquire. Fortunately, CMU has an advantage here: since the University (and Carnegie Tech before it) has been involved in technological research for many decades, our library happens to own a large number of older books on computation. Books that were bought in the 1950s or 60s to keep up with cutting-edge research are today important historical documents. My task was to go through the Origins of Cyberspace catalog, identify which items the library already owns, and help decide whether books in general circulation should be transferred to Special Collections.

Working on this project over the past few months has been enjoyable. Searching through the library catalog hundreds of times to see what items we hold was monotonous, but in a good way: graduate school involves a lot of deliberate, heavy thinking, and switching over to repetitive data entry for an hour or two can be relaxing. I’m already quite familiar with the university library system (as of this writing I have 47 books checked out), but going through so many old or rare books gave me a better sense of how the catalog system works. I only ran into a few technical problems. (Did you know that the library sometimes stores multiple copies of the same book offsite, but that the online catalog only allows users to request one of these offsite copies at a time? This makes some sense, but it makes it hard to gather all of the library’s copies of particular books to compare which are in better condition than others.)

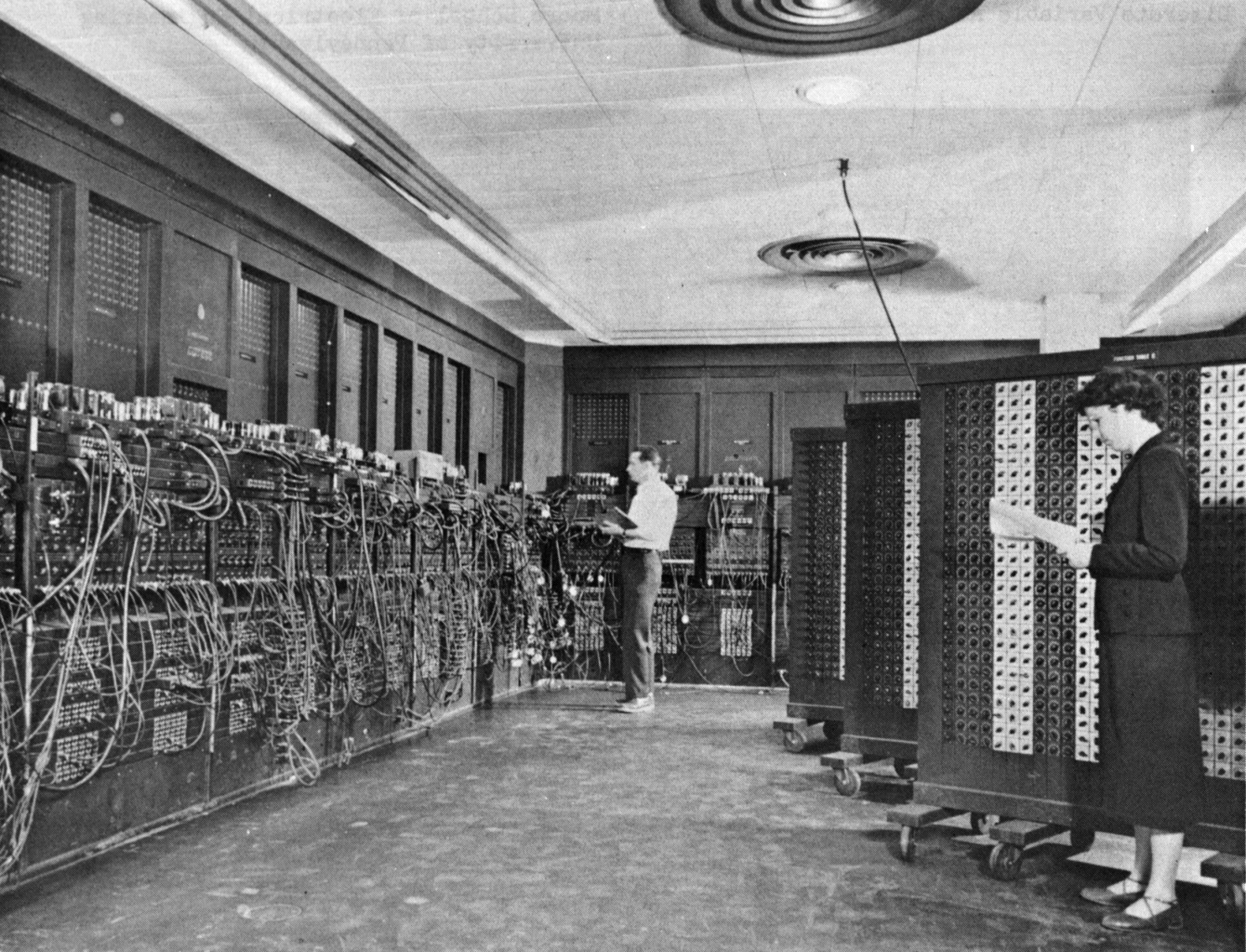

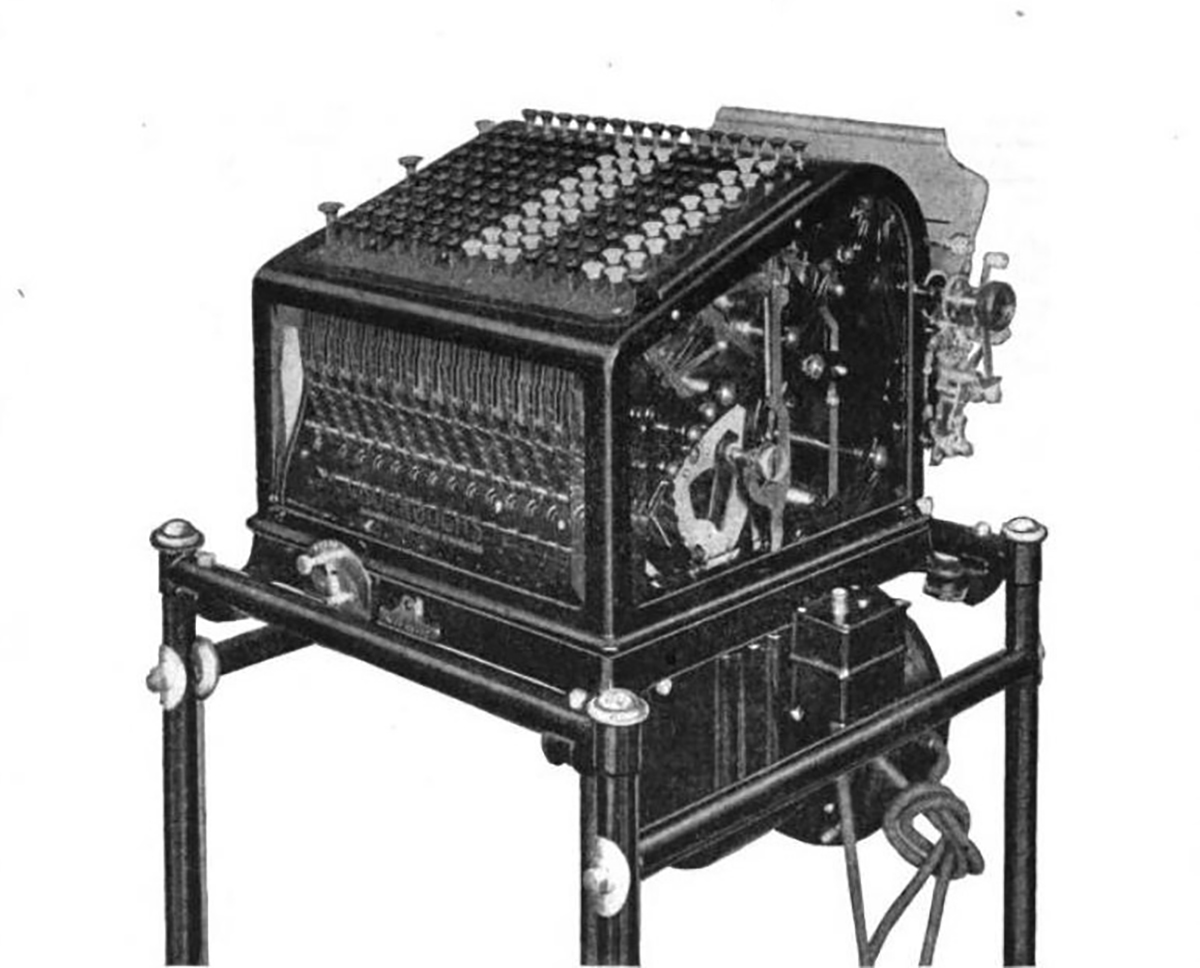

Collecting the Origins of Cyberspace catalog also offered a crash course in the history of computing. I had already heard of many of the major names in computing--Charles Babbage, Alan Turing, Grace Hopper--but I’ve never studied this history formally and a lot of the lesser-known content was new to me. Much of the history of computing before 1940 took place in private businesses, where accounting and recordkeeping are important. This is a bit obvious in retrospect, but I was surprised to see so many advertisements and manuals for accounting machines from the 1920s and 1930s listed as historically-significant documents.

How well does Carnegie Mellon’s library do in the history of computing? Out of more than 300 items from the Origins of Cyberspace that I checked, CMU holds about 70, most of them from the mid- to late-twentieth century. Given how rare or ephemeral some of these texts are, that’s not bad at all! Some of the more valuable items in the collection include Alexander Graham Bell’s original paper on telephone technology (held in the Posner Memorial Collection) and a copy of the operating manual for the Harvard Mark I, written by Grace Hopper and Howard Aiken (stored in the Special Collections reading room on the fourth floor of Hunt). It was especially exciting to find important books shelved outside of Special Collections. These were likely books that the library has held for decades but never moved from the stacks in Hunt. We have the proceedings of four of the Macy Conferences, for instance--famous for their role in the history of cybernetics--that have been sitting on the third floor of Hunt for who knows how long. Another example: CMU’s offsite storage holds several volumes of the journal Mathematics of Computation, including one where J. W. Cooley and John Tukey’s 1965 article on the fast Fourier transform algorithm was originally published. The article is both financially valuable and at the time represented a major step forward in calculation speed.

Once we had identified which items CMU already owns, the next step was to collect them in one place, evaluate their condition and rarity, and decide which ones should be transferred to Special Collections. I was able to track down 48 copies of books and journals (mostly in offsite storage) and move them up to the Rare and Fine Books Rooms to be evaluated. Sam Lemley, Curator of Special Collections, has started to go through these items and decide whether they are eligible for transfer to Special Collections. Many of these books get rejected -- typically because there is already a higher-quality version held in Special Collections or because the book isn’t rare enough to justify inclusion. If a book does get marked for movement to Special Collections, it will stay on the fourth floor and eventually have its online library catalog information changed.

I hope that this accounting of the library’s resources will be useful to future researchers. It’s true that copies of many of these texts are available online, but not all of them are, and in historical research there’s often no substitute for an original paper copy. More than that, I hope that thinking about the history of computing through library materials will remind us what it means to work at a place like Carnegie Mellon. You probably already know that researchers at CMU have made important contributions to the history of technology and computing. But there’s more to this history than buildings named after famous professors or numbers of Nobel Prize winners: the history of computing is all around us, hiding in unexpected places in the library stacks.

by Posner Curatorial Intern Jamie Leach

Feature image by Markus Spiske on Unsplash