Looking through the Posner Memorial Collection as a speaker of a single language—or even two or three languages—can be daunting. English only became the standard language of international science in the twentieth century. Venture into earlier eras of science and you’ll quickly discover works written in French, German, Italian, Latin, Arabic, or Chinese. Since the Posner collection focuses on first editions, there are few English translations of existing works. I was thus surprised and intrigued to find Silvanus P. Thompson’s 1912 translation of Christiaan Huygens’s "Traité de la Lumière (Treatise on Light)," originally published in 1690.

Huygens’s "Treatise" was one of two foundational works in optics—the study of light—published around the turn of the eighteenth century. The other was Isaac Newton’s "Opticks" (1704), written around the same time as Huygens’s work but published fourteen years later. Humans had observed how light moves and reflects off surfaces since ancient times, but Newton and Huygens wanted to move beyond description and explain what light really is. They approached the topic from totally different perspectives.

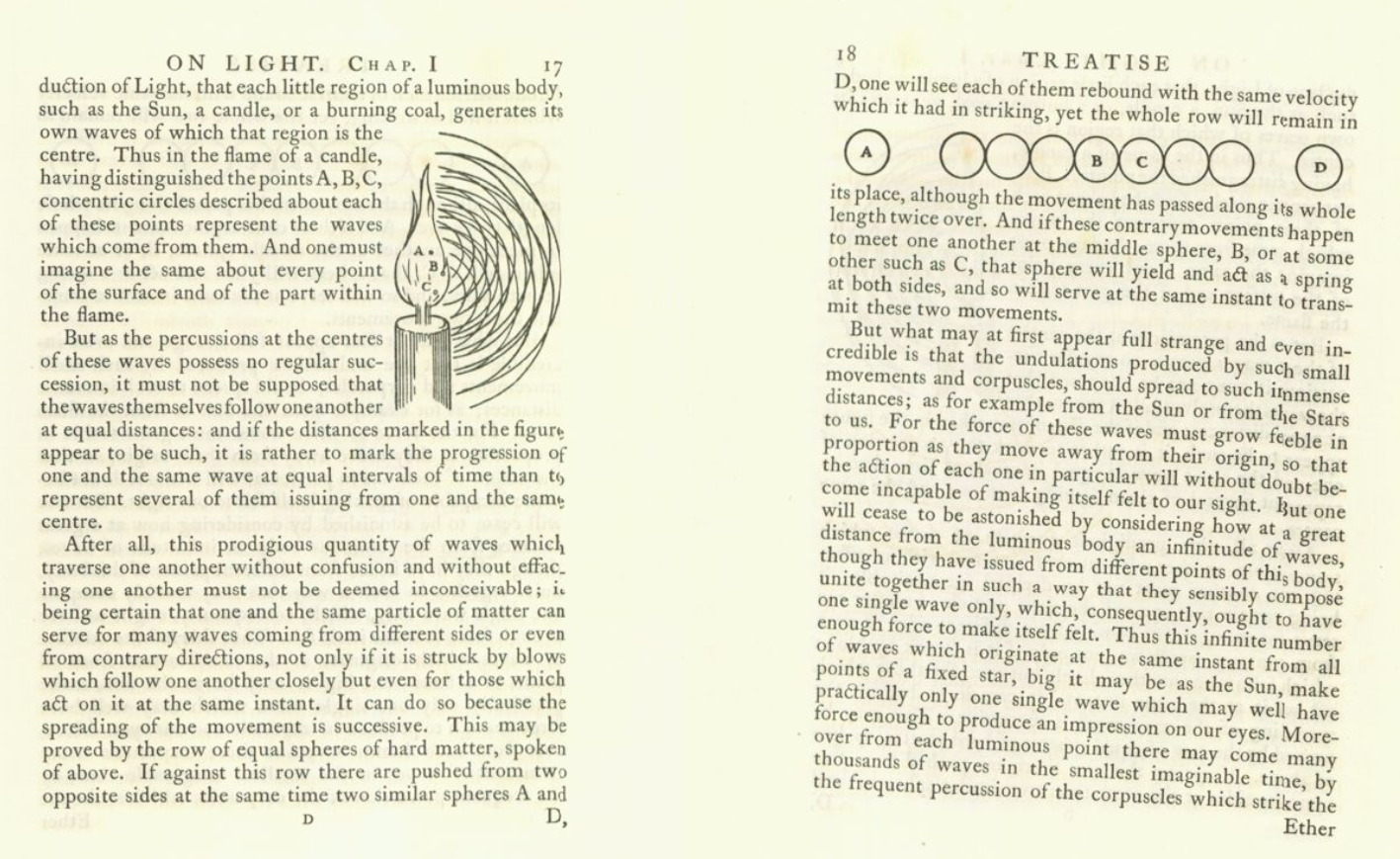

Newton’s "Opticks" is famous for its treatment of color, showing that white light is actually a mixture of different colors of the rainbow. Less well-remembered is his belief in the corpuscular theory of light (also called the projectile or emission theory): at a basic level, Newton thought, light was composed of tiny particles that shot out of a source and moved in straight lines. Huygens, on the other hand, believed that light consisted of waves spreading out from a source in all directions. Just as sound waves consist of vibrations of the air, light waves consist of vibrations in another medium, the ether, which permeates all physical space. While Huygens initially rejected Newton’s theory of color, his wave model could explain phenomena such as diffraction, which Newton struggled to handle.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, most physicists had accepted Huygens’s wave interpretation—a series of experiments by Thomas Young and Augustin-Jean Fresnel had shown that beams of light can interfere with one another, just like water waves or sound waves. So, if Huygens’s work was so successful, why did it take 200 years for the Treatise to receive an English translation? Sylvanus Thompson guessed that it might stem from the anglophone world’s chauvinistic attachment to the Englishman Newton. Besides his translation work, Thompson was interested in pedagogy, and he disliked the traditional distinction between geometric optics and physical optics—first telling students that light travels in rays, and then later revealing that it actually travels in waves. In his own public lectures on light, Thompson chose to follow the wave model from the beginning, an approach he thought might “seem strange to the sedate student whose knowledge of optics has been acquired on the narrower basis of the orthodox textbook.” [1]

But beyond Thompson’s personal opinions on Newton or pedagogy, his translation of the "Treatise" came at a unique moment in the history of physics. In the 1890s, physicists discovered x-rays and radioactivity, and the idea of invisible energy propagating through space caught the European public’s imagination. Thompson continued to write about an ether through which light travels, but Einstein’s theory of special relativity (published in 1905 but not universally-accepted as of 1912) gave a very different account of how light moves. And many physicists throughout the 1900s and 1910s laid the foundations for quantum theory, showing that light could only carry energy in discrete chunks—ironically calling the wave theory of light into question just as Thompson introduced Huygens’s work to English speakers.

What I find most interesting about the translation of Huygens’s "Treatise" is how old-fashioned it feels, despite being published as modern physics came into being. Thompson recreated the format of the original French title page, giving the impression that the English version might have been published in the seventeenth century. Thompson’s translator notes comes immediately after Huygens’s original preface and begins with the same decorative initial letter, as though author and translator were speaking with the same voice, two centuries apart. Thompson was not a traditionalist—he followed and was excited about new discoveries in electromagnetism and radiation (though he might not have grasped the importance of relativity and quantum theory before his death in 1916). Yet he chose to present his translation within the aesthetics of classical physics, even as other researchers were moving beyond Huygens’s ideas.

[1] Sylvanus P. Thompson, "Light, Visible and Invisible: A Series of Lectures Delivered at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, at Christmas, 1896, with Additional Lectures," 2nd ed. (London: Macmillan, 1910), v.

by Jamie Leach, Posner Curatorial Intern

Feature image by Braxton Apana on Unsplash.