In an early photograph, a six-year-old Rachel McMasters Miller stands confidently on an artificial stone, a photographer's prop contrived to bring nature into the studio. She holds a diminutive basket of flowers in the crook of an elbow and wears an expression that suggests she's well aware of what real stones and flowers look and feel like—and these aren't they.

Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt (1882-1963) was a natural collector, whose quarry (botanical books from the twelfth to the nineteenth centuries) reflected a lifelong interest in books and horticulture. 'Botanical books,' Rachel Hunt wrote in 1958 with some understatement, 'have been mixed with all my pleasures.'

Calling on considerable resources—intellectual, cultural, and financial—Hunt acquired what I would argue remains the best collection of botanical books ever assembled by an individual in this country. Hunt's prized books on botany and horticulture—ranging from an early medieval poem handwritten on vellum that describes the medicinal uses of herbs to lavishly illustrated books by pioneering botanist and entomologist Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717)—were given in 1961 to form the library of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation on Hunt Library's fifth floor. The rare books that remained, including Hunt's collection of fine bindings, were given to form CMU's Special Collections, housed one floor down in a room built for the purpose.

The fate of Hunt's books is fitting: they sit in a building that's not only named for her and her husband, Roy A. Hunt, but faces Phipps Conservatory and its abundance of plants across the green expanse of Schenley Park. A lifelong gardener, Hunt no doubt appreciated the symmetry of this arrangement.

The kinship between plant and book collecting is not self-evident, yet both require an intense regard for species, genera, and morphology. Both also claim distinctive nomenclatures and taxonomies of bewildering specificity. Rachel Hunt, for her part, could recite Linnaean binomials and bibliographical terminology in the same sentence. Hepatica nobilis and folio in eights were, for her, equally legible.

Bibliography and botany are sciences of description: while the botanist attends to stamen, sepal, and calyx, the bibliographer detects crushed morocco, chainlines, and serifs. Bibliophilia and biophilia even seem to share a lexical root; bio- and biblio- are visual rhyme words, if not immediate etymological kin. The horticulturalist and the bibliophile also share a fanatical (often ruinous) commitment to completism: the collector of books commits herself to seek interminably one more rarity, just as the collector of plants seeks one more specimen or uncommon bloom. So too, the book collector and the plant collector are creatures of refined taste, with faculties honed by years of exhaustive hunting. Rachel Hunt stood astride these disciplines and wore both identities with a natural ease.

Hunt's bookish horticulturalism went beyond her collecting. It was also reflected in the way she blurred the boundary between her garden and her library, both cherished spaces at Elmhurst, the Shadyside home where she lived with her husband and their four sons. At Elmhurst, Hunt sought to recreate the lavish architecture of the eighteenth century, a period defined by grand domestic spaces where the library augmented the garden and house, and the house and library reflected back the beauty and abundance of the garden: 'The eighteenth century,' Hunt wrote, 'was an era of great houses, regally furnished, with superb paintings, beautiful china, and tapestries, with large well-used libraries. Their grounds were of equal splendor, attractively landscaped and meticulously maintained.' Hunt's tastes in house design also influenced the appearance of the Hunt Institute's reading room. With its ornate carpets, floor-to-ceiling bookcases, and carefully curated antiques, it evokes and mimics the eighteenth-century libraries Hunt so admired.

Despite Hunt's looming influence on horticulture and book collecting, however, for most of the twentieth century these fields were realms of male expertise and cultural status. The literature of the period is chock full of references to ‘plantsmen' and ‘bookmen', but comparatively few book- or plantswomen. As writer and antiquarian bookseller Allison Devers and others have noted, the antiquarian book trade has long catered to male collectors, booksellers, and curators, and the same could be said of horticulture: book culture and plant culture have tacitly excluded women.

Rachel Hunt didn't shrink from saying the quiet part out loud, though: along with six other bookwomen, she founded the Hroswitha Club in 1944 (named for the tenth-century author and cannoness Hrotsvitha) after learning that the Grolier Club, the oldest bibliophilic organization in the U.S., would not accept women. She and her co-founders Belle da Costa Greene, Anne Lyon Haight, Sarah Gildersleeve Fife, Ruth S. Granniss, Eleanor Cross Marquand, and Henrietta C. Bartlett—all curators, collectors, librarians, and scholars with double-barrelled names—were not content to leave the books to the men.

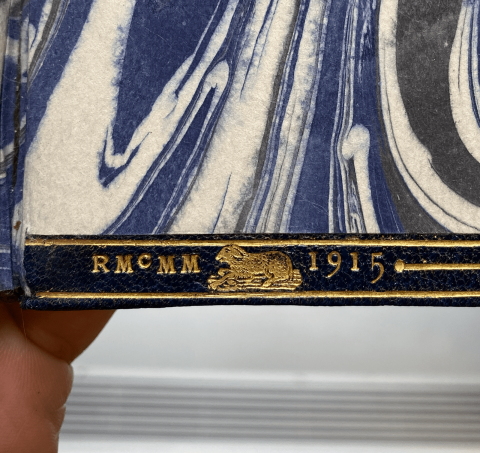

Hunt was also a craftswoman. Trained in the art of bookbinding by her friend Euphemia Bakewell (1870-1921), Hunt established a binding workshop called the Lehcar Bindery (Lehcar is ‘Rachel' reversed) in a sunlit studio in her home. Many of her bindings, done with characteristic attention to finish and form, still adorn books in CMU's Special Collections. Hunt's bindings can be identified by her gold-stamped insignia, shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Rachel McMasters Miller Hunt's monogrammatic binding stamp usually appears at the bottom of the backboard of her expertly bound books. Shown is Hunt's copy of The book of Sir Galahad and the achievement of the adventure of the Sancgreal (London, 1904) PR2043 .A75 1904.

Hunt Library was dedicated 59 years ago on October 10, 1961, and as it begins its 60th year this month, Rachel Hunt's story still resonates. If you'd like to learn more about Hunt and her collection, The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation has done excellent work documenting Rachel McMaster Miller Hunt's legacy in Pittsburgh and at CMU. For more on her activities as a collector and philanthropist, see their ‘About' pages. I am indebted to these pages as well as to Charlotte A. Tancin, Librarian and Principal Research Scholar, Terry Jacobsen, Director of the Hunt Institute, J. Dustin Williams, Archivist and Senior Research Scientist, and Nancy Janda, Assistant Archivist, for the information contained in this blogpost. Their work and the collection they oversee are a fitting monument to Rachel Hunt's memory.

Top image: Rachel Miller (Hunt, 1882–1963), Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, September 1888, photograph by B. L. H. Dabbs, Hunt Institute Archives portrait no. 46.