In mid November, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the merger between Mellon Institute of Industrial Research and Carnegie Institute of Technology by highlighting all the pioneering, creative and passionate individuals who have made CMU what it is today. One of those visionaries was Robert Kennedy Duncan, a professor and chemist who conceived of the Industrial Fellowship system, which was the inspiration for, and foundation of, the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research.

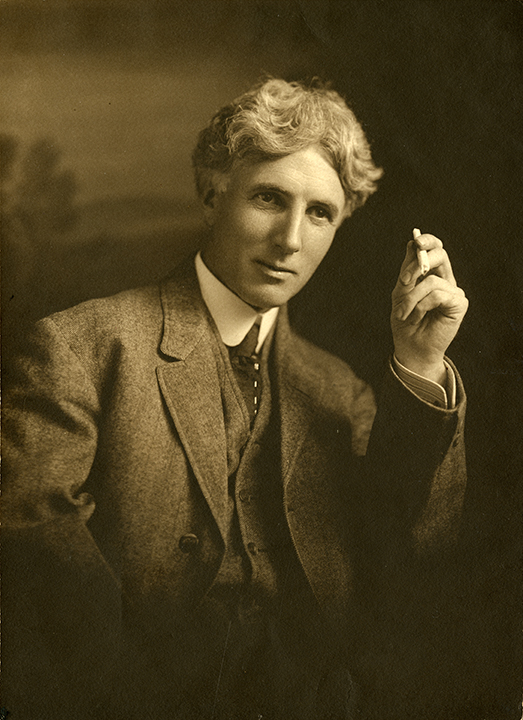

Duncan was born in 1868 in Brantford Ontario, a small Canadian town located not too far from Lake Erie and Alexander Graham Bell's family estate where Bell invented the telephone. Duncan became interested in science at an early age and graduated with a B.A. from the University of Toronto in 1892 with honors in physics and chemistry. From there he completed a year-long fellowship in Chemistry at Clark University and then began teaching physics and chemistry at Academic High School in Auburn, NY.

In 1895 he left Auburn and accepted a teaching position at Dr. Julius Sach's Collegiate Institute in New York City. While he was in New York he pursued supplemental graduate work in chemistry at Columbia University between 1897 and 1898. After studying abroad for a year, he secured a chemistry professor appointment at Washington Jefferson College, in Washington, PA. Between 1901 and 1906, Duncan taught physics and chemistry and was known for instilling a sense of enthusiasm and excitement for science in his students. Outside of school, Duncan found time to conduct research and devise new processes for industrial clients, which resulted in several new patented discoveries in phosphorus and glass making.

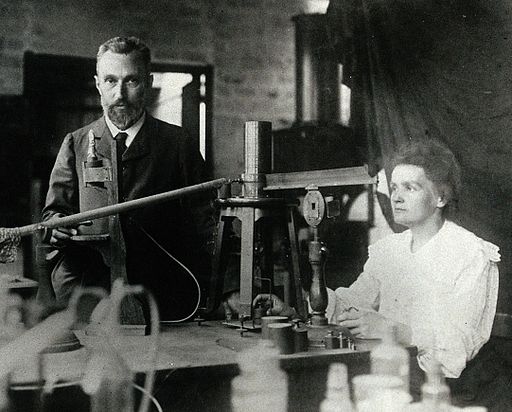

Through his experience as a teacher Duncan realize that there was a great need for literature that explained that latest scientific discoveries in a way that a normal person could easily understand and began to dedicate more of his time to chronicling and decoding the scientific papers of the time. By about 1900 he had become a frequent contributor to several New York periodicals, including the New York Evening Post. After Duncan's articles had started to attract attention he was sent abroad in 1901 by McClure's Magazine, a monthly illustrated periodical known for its investigative journalism, to study radioactivity with Pierre Curie and Marie Curie in Paris. This was just two years before they won the Nobel Prize in Physics, "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel".

Two years later, A.S. Barnes & Co., a leading publisher of textbooks and other general interest books, assigned Duncan to collect material that would be suitable for use in a new manuscript on new scientific knowledge. He also chronicled the many advances in science in Harper's Magazine, and he wrote several books: The New Knowledge (1905), The Chemistry of Commerce (1907) and Some Chemical Problems of Today (1911).

Eventually Duncan became widely known as an interpreter of science. 'He could impart life to the most abstruse scientific facts and make them of intense interest to laymen', William Hamor, the Assistant Director of Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, wrote in 1929. 'He wrote with unique charm of style and remarkably clear explanatory power, and thereby, through his published articles and books, aroused a widespread realization of the importance and utility of science.'

While attending the Sixth International Congress of Applied Chemistry in Rome in 1906, Duncan conceived of the 'Industrial Fellowship' program. By this time, Duncan had made several research trips to Europe, during which he visited factories, laboratories, and universities. Through these trips he had become impressed with the cooperative spirit that existed between industry, technology and science. He had also become aware of the absence of scientific research methods in American industry and the need to improve efficiency in manufacturing. To solve these issues, Duncan developed the Industrial Fellowship program where trained scientists could be employed to solve the immediate research needs of industry, while simultaneously advancing the greater good of mankind.

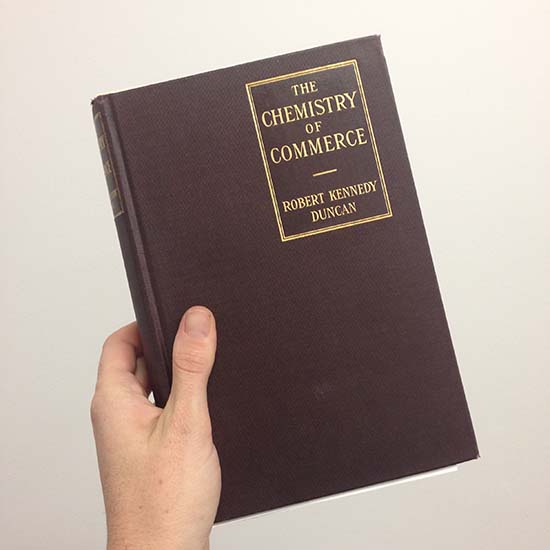

Upon returning from Europe Duncan dedicated his life to making the fellowship system a reality. In 1907 he accepted a position at the University of Kansas as the chair of industrial chemistry. There he established the first Industrial Fellowship and published The Chemistry of Commerce, in which he outlined the Industrial Fellowship program and argued 'how absolutely applicable modern science is to the economy and progress of manufacturing operations.'

A couple of years after Duncan published The Chemistry of Commerce, a copy of the book fell into the hands of Andrew W. Mellon. Inspired by Duncan's appeal for industry to try something new, Andrew W. Mellon, along with his brother Richard B. Mellon and Samuel McCormick, then the Chancellor of the University of Pittsburgh, invited Duncan to Pittsburgh to discuss the possibility of starting an Industrial Fellowship program at the University of Pittsburgh. The city was a bustling industrial center which offered Duncan new opportunities, so in 1911 a fellowship program was inaugurated in Pitt's Department of Industrial Research under Duncan's leadership. Two years later, in March of 1913, with funding from the Mellon brothers, the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research was formally established at the University of Pittsburgh.

Sadly, Duncan passed away on February 18, 1914 at the age of 45, before he could see the Mellon Institute grow into a pioneering, independent industrial research firm. Duncan's vision for a better future, his love for science, his selflessness, and his zeal for 'his boys' – the many scientists he mentored and worked along side with – set the Institute on an unwavering course that would shape the Mellon Institute and the industrial research landscape for decades to come.

To learn more about Robert Kennedy Duncan and the Mellon Institute of Industrial Research, check out previous posts on Scotty Tales, the university archives blog. Also see 'Digging Into The History of Mellon Institute of Industrial Research' exhibition on the 2nd Floor of Hunt Library. And if you have any questions, don't hesitate to ask! Contact the University Archives at archives@andrew.cmu.edu or 412-268-5021.

by Emily Davis, Project Archivist