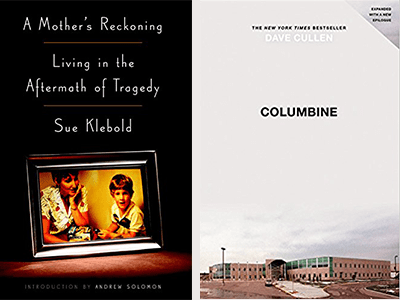

A Mother's Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy by Sue Klebold

I didn't plan to review this book, but halfway through my reading, news broke of the Parkland, Florida shooting. So, sadly, the topic is freshly relevant.

As the memoir begins, Sue Klebold gradually learns that her son Dylan and his friend Eric Harris opened fire in Columbine High School. She is overwhelmed with horror, struggling to reconcile this with what she knows of her intelligent, quiet teenage son. The more she hears about the massacre, the more she prays not for her son's life, but for his death.

In the months to follow, Klebold mourns for Dylan and for his victims, receiving sympathy and comfort from some, anger and hate mail from others. Unable to join support groups for families of suicides because of legal ramifications, Klebold is paralyzed with grief, shame and guilt. Eventually she returns to work part-time at her community college job, regaining some physical and emotional strength.

Meanwhile, the police investigation continues. Dylan's depression had shown only in occasional irritability; his friend Eric knew how to charm and manipulate adults. The pair had one brush with police in their junior year, and served time in a probation program. Their senior year seemed to go smoothly, even as they planned their attack for April. Seeing the 'Basement Tapes,' Dylan's mother says, 'He and Eric were preposterous, posturing, giving a performance for each other and their invisible audience.' She is shocked by the 'hate-filled, racist, derogatory words … never spoken or heard in our home.' Police who searched Eric and Dylan's rooms went home to search their children's rooms 'as never before.'

Reconstructing Dylan's life before the shooting, Klebold says she didn't realize her son's 'brain illness.' She urges parents to recognize symptoms that children and teens display, and to seek treatment. (On Feb. 26 of this year, the American Academy of Pediatrics advised parents to have children screened yearly for depression; the high rates of teen suicide make this advice timely.) Klebold says, 'Of course it would be easier to help depressed teens if they were nicer to be around … If only they looked like the kids in the pamphlets do: clean-cut and attractive, staring out a rainy window with a wistful expression, chin propped on a fist! More commonly, though, a disturbed teenager will be unpleasant: aggressive, belligerent, obnoxious, irritable, hostile, lazy, whiny ... But the fact that they're so difficult … does not mean they do not need help.'

Klebold also clarifies that mental illness in itself does not lead to violence, and encourages more openness about our 'inner storms.' She mentions only briefly the danger of having guns easily accessible to people who are 'at their most vulnerable.'

I had some difficulty with Klebold's focus on her son's 'suicidality' over his participation in homicide. Still, I admire the courage it took to write this memoir. It's worth reading for her insights on how evil can seem so recognizable in retrospect, and so hidden right before our eyes.

Columbine by Dave Cullen

After being immersed in Sue Klebold's tight, almost claustrophobic focus on her son, I was curious to re-read Dave Cullen's brilliant, more comprehensive work of reportage. Columbine takes a panoramic view beyond the high school to the foothills of Colorado and the town of Littleton, to local churches and police, and the national media. Moving back and forth between the shooting and the years leading up to it, introducing not only the Klebolds and Harrises but the victims and their families, Cullen builds an absorbing story of missed cues, confusion and misinterpretation.

We know now that shootings need to be stopped as soon as possible. During the siege at Columbine, hours went by, victims dying as police and the media wrongly assumed a hostage event. 'We saw fragments,' Cullen writes. 'An army of police held at bay suggested an equivalent force inside … Killers seemed to be everywhere … The data was correct; the conclusions were wrong.' The media speculated, using the bits of information they had. Trench Coat Mafia. A religious martyr. Outcasts versus jocks. Bullied kids who suddenly snapped. None of these myths were true, but they caught on. Most importantly, nobody was specifically targeted, and there was no trigger. 'Everyone was supposed to die … [Columbine] had not really been intended as a shooting at all. Primarily, it had been a bombing that failed.'

Many personal stories bring the pages of Columbine to life – the FBI investigator, the high school principal, the victims/survivors, the parents of killed and wounded students, the families of murdered teachers. We hear so many survivor stories after school shootings, but Cullen's use of detail makes each struggle unforgettable. We hear from the wife of a fatally wounded teacher; waiting for news, she watches as friends come to her home, thinking that she should have vacuumed. We can feel the survivor's guilt of the student who ran without stopping to help a student who fell just beside her. And there is the injured teen whose recovery is complete – except for a dragging left leg and an odd handshake, finger poking awkwardly into your hand.

With access to both boys' diaries, Cullen gives us glimpses into Eric's pervasive contempt and hatred, and oddly enough, Dylan's constant longing for love from a girl he hadn't even spoken to. Psychologists who studied the boys' friendship concluded that Eric's destructive energy combined fatally with Dylan's depressive anger. One critic compared Cullen's work to Capote's In Cold Blood, which struck me as exactly right in terms of the deadly combination of personalities, and as a compliment to Cullen's vivid storytelling.

Columbine also includes a list of adolescent behaviors that parents, teachers, and counselors should watch out for. I'd recommend Columbine and A Mother's Reckoning just for these warnings. It's fascinating, as well, to compare both narratives as they intersect. Of the two, Cullen's work was the more graceful and effective; Klebold's, less expertly written, has its own raw power. Both offer so many insights into the gaps between our expectations of children, parents, school administrators, and police, and the reality of what we overlook, assume, mistake, and miscommunicate. Hopefully the more we learn about 'brain illness,' parenting, and policing, the more these gaps can be closed.

By Jan Hardy, Cataloging Specialist