Blue Horses (New York: Penguin Press, 2014) is a slight book of deceptively simple poems, 'something/inexplicable/made plain' as Mary Oliver says in 'What We Want.' It's only when you think further into them that you realize these poems have a lot to say. Oliver's spirituality, like her imagery, springs from the natural world and the senses. I can remember images from Oliver's books I've read long ago, and I'll remember these, too – the 'fox on his feet of silk' ('The Fourth Sign of the Zodiac') and the water 'dashing its silver thumbs/against the rocks' of 'Stebbin's Gulch.'

Writing about nature realistically leads to writing about death as well, and Oliver opens her book with 'The slippery green frog/that went to his death/in the heron's pink throat' ('After Reading Lucretius, I Go to the Pond'). The poet accepts both the frog and the heron as her brothers, and ends 'My heart dresses in black/and dances.' Oliver mentions other poets and thinkers like Lucretius, Rumi, and Whitman, but you don't have to be a scholar to appreciate her poems, just like you don't need a degree in biology to enter her landscapes.

What I love most about Oliver's poems is her delight in, and praise for, the natural world, as in 'Loneliness' ('Oh, mother earth,/your comfort is great, your arms never withhold/…Oh, motions of tenderness!'). In 'Forgive me,' the persona apologizes for her lateness because she just had to stop to appreciate beauty and 'holiness.' In 'Good Morning,' when the persona says 'It must be a great disappointment/to God if we are not dazzled at least ten/times a day' I recalled Shug's observation in Alice Walker's The Color Purple: 'I think it pisses God off if you walk by the color purple in a field somewhere and don't notice it.' You get a sense of the poet walking through the world, continually observing, with a thankful spirit.

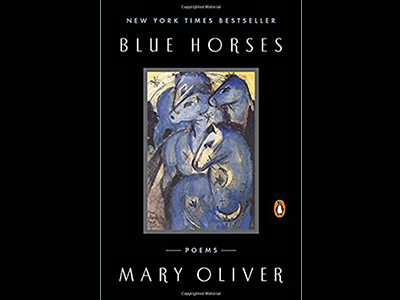

The title poem, 'Franz Marc's Blue Horses,' allows the poet, and the reader, to enter the painting and experience 'the desire to make something beautiful' which 'is the piece of God that is inside each of us.' Oliver grieves the wartime death of the painter, comforting the blue horses and the reader, praying 'Maybe our world will grow kinder eventually.'

Sometimes Oliver's everyday diction drags a bit, but those instances are few. More often, I'm engaged and entranced when Oliver wants to meander, as in 'If I Wanted a Boat' ('I would want/a boat I couldn't steer'). And I love the self-deprecating fun of 'What I Can Do,' 'First Yoga Lesson,' and 'On Meditating, Sort Of.' Mary Oliver's poems have a cheerful ditziness ('On Not Mowing the Lawn'), a reverence for both life and death, and an ability to see beauty and holiness in the ordinary. 'I don't care how many angels can/dance on the head of a pin' she says in 'Angels.' 'It's/enough to know that for some people/they exist, and that they dance.'

By Jan Hardy, Cataloging Specialist